Editor’s Note: Responses have been edited for clarity and concision.

Many young adults face the reality that the American housing market is much less accessible than it used to be, and some can no longer afford the luxury of living alone.

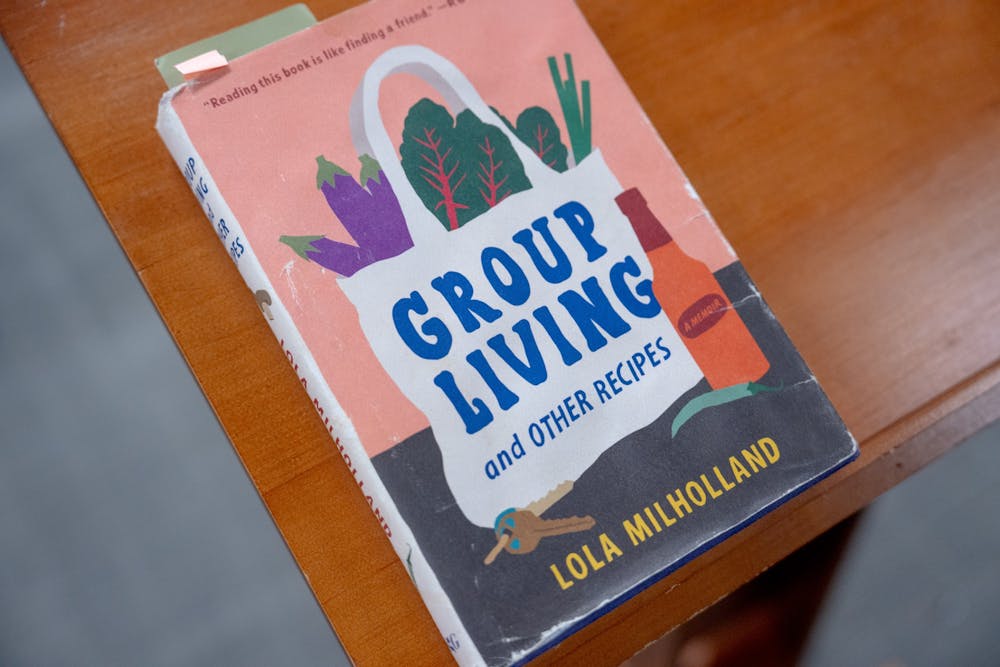

This is the point that author and food business owner Lola Milholland illuminates in her book, “Group Living and Other Recipes.” Milholland served as an editor for “Edible Portland” magazine and work has also appeared in “The Guardian” and “Time Magazine.”

Milholland says American society should embrace sharing a living space with non-romantic partners, not only as a college student or elderly person, but at any age.

The Beacon spoke with Milholland before her Nov. 4 campus lecture on group living. She discussed her work in food ecology and communal living, and their relevance to current world events like SNAP benefit cuts.

The Beacon:

“What inspired your work in food ecology?”

Lola Milholland:

“I was raised here in Portland, and my parents worked in natural foods grocery stores. My mom was the head of sales and marketing at Organic Valley and helped it flourish from a small to a large company, without taking advantage of the company’s success. This was very inspiring to me because it was a co-op with a mission to support its members and farmers. Watching that gave me an insider’s view on how food businesses are run and an orientation around food businesses that have a powerful environmental and social ethic, which made food central in my life.”

The Beacon:

“What is your business, and what does it provide?”

Lola Milholland:

“I have this business called Umi Organic, which we started in 2016. I have studied Japanese since I was five, and lived in Japan, which has a very place-based food culture. Meaning, as you travel the country, you get to experience food through the lens of that place and its environment. So I came back to Portland and realized there were no Japanese-style noodles being made using local flour. I decided I wanted to make a product inspired by Japanese noodles, with a commitment to place-based production.

“We make two products: a ramen noodle made with Oregon-grown whole grain barley flour and a Yakisoba noodle made from whole grain Durum and Edison, which is developed for this region. One mission of the company is to support local farmers and the other is to make nutritious, delicious food available to public school students, which has become the beating heart of the business.”

The Beacon:

“What is the main takeaway from ‘Group Living,’ and why did you choose to write it?”

Lola Milholland:

“I have always loved writing because when I write, I give words to what I care about. I write about everything, including the communal home I live in. I live in a big, old 1906 home in Portland with my boyfriend, my brother, my roommate and other people who come through. I found it fascinating that I was getting older, nearing 40, but still living communally. Among my generation, when you think about group living, you think cult groups, college housing or retirement homes, but not four adults with jobs sharing space in that way. It seemed deeply unusual to me, but I realized it’s becoming less unusual because the cost of housing is becoming so extreme. I did local and widespread research and found that one in three adults currently live with a roommate of some kind. I wanted to describe this in a way that would open people to thinking about communal living differently [and] to recognize that there’s a galaxy of approaches to living.”

The Beacon:

“Why is the concept of group living significant in this day and age?”

Lola Milholland:

“The home ownership system in America is deeply intertwined with systematic racism, where non-white people struggle to accumulate generational wealth. We need new housing policies that make safe, affordable housing a human right. Also, very few people actually live in a stereotypically American [nuclear household]. So how are we living? I think communal living is a survival strategy within a really tumultuous economy.”

The Beacon:

“How does your work in food ecology connect to your research on group living?”

Lola Milholland:

“When you live in a communal space, you have to share food resources. That can mean sharing an oven, a toaster or sharing meals together. My research on group living led me to think about what it means to be in a community that sees itself as a whole. The family I live with is not like a traditional nuclear family, but we take care of each other in a really powerful way, and we are all part of this organism, which is our home.

“In my book, I explore how the patriarchy has enforced that most of the domestic burden falls upon women in a couple. In my house, we all feed each other, buy groceries, clean and take care of one another. It’s important to see whatever microcosm you’re in as part of a larger system. That is food ecology.”

The Beacon:

“What is the influence of economics and politics on you as a food ecologist and business owner?”

Lola Milholland:

“Food ecology defines our culture because we live in a place with a profound farming community. Do we want a super data center to maintain our farmland? How do we want people to be able to access food? As food prices rise, how do we ensure that people get what they need to eat? Right now, SNAP benefits are about to disappear, which is an example of how what’s happening nationally will have an immediate and disastrous impact on our smaller community. Food ecology is centered upon the very health, identity and structure of our communities in all ways.

“Food culture gives us identity and knits us together because there is something about sharing means with other people that is one of the most human ways to interact. Sharing meals is the foundation of most cultures and is an important way to build your personal culture. I don’t think that if everyone in America sat down at one giant table, and we all had a meal, that all our problems would be solved. But I do think that we live in a place where loneliness is excessive; it’s called the loneliness epidemic for a reason. People are looking for a sense of connection and the fastest way to do that is by sharing meals with people. And that is where food ecology and group living intersect.”

The Beacon:

“What have you prepared to speak about at your lecture tomorrow?”

Lola Milholland:

“I want to highlight the importance of food ecology and group living to a college audience because at this age, you are just beginning to formulate the way you see the world and integrate it into your active participation in society. You are all currently living and interacting with some communal system and after this, [you] will go on to decide how you want to build a home. I look forward to learning from this talk the way that youth conceptualize their idea of group living, and how you will go on to shape our world.”

More information about Milholland’s work on food ecology and group living can be found here.

Clara Pehling is a News Reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at pehling28@up.edu.