Since 2004, philosophy professor Alejandro Santana has introduced to students his logical fallacies unit with a distinct artifact: a glass jar of rancid grease.

Santana uses this jar — in which oil and animal fat have now festered for over two decades — as a device to teach critical thinking.

“Accepting an argument based on a fallacy is as bad for your intellect as taking a swig of the oil in that jar would be for your body,” Santana said.

The jar represents finding one’s path, a journey Santana has also undergone outside the classroom.

For the past 15 years, he’s engaged in the process of learning more about his heritage, which he shares through his metaphysics class on Native American philosophy and his advisement of clubs like Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA), Native American Alliance (NAA) and the Ethnic Studies Club.

He encourages students to do the same by exploring their indigeneity and decentering their colonized identity.

“It was part of the colonial project to, in some ways, erase indigenous culture,” Santana said.

Growing up, Santana didn’t hear much about his indigenous heritage from his parents — his father being from Durango and mother from Ciudad Juarez. But Santana’s fascination with his roots led him to learn as much as he could about his indigenous identity once he began his teaching career.

Santana’s journey of connecting with his indigeneity started when he attended a Native American Youth and Family Center (NAYA) event during his sabbatical in 2010.

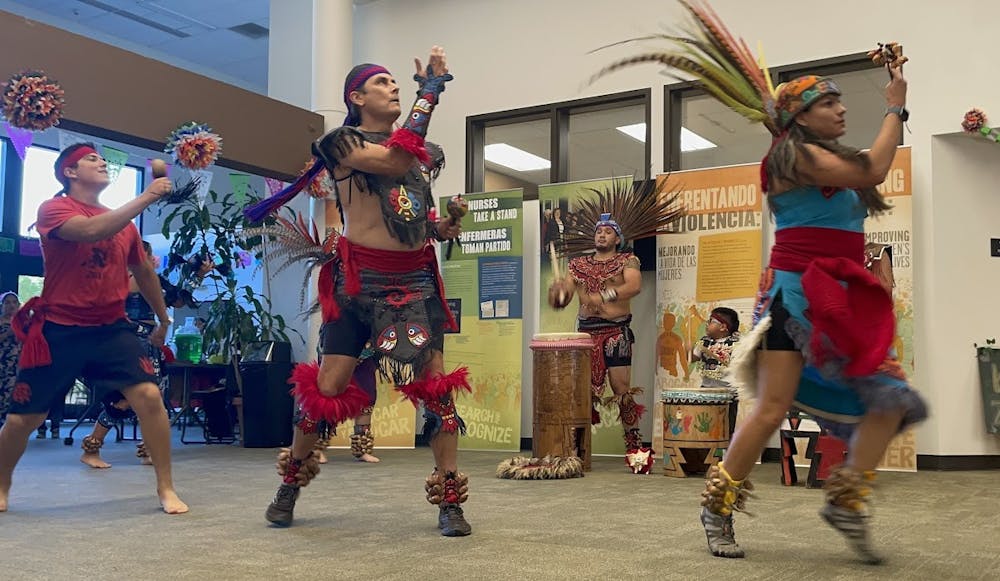

It was here where, allured by the familiar scent of burning copal, his interest in Danza Azteca — a cultural dance and art form from Mexico — was sparked.

Santana with Danza Ateca group, Mexica Tiahui, at a presentation in Forks, WA. Photo courtesy of Alejandro Santana.

Since then, Santana has been involved with Mexica Tiahui, the Pacific Northwest’s first Danza Azteca group.

For Santana, Danza Azteca wasn’t something he wanted to learn about from a detached perspective, but something he wanted to study through first-hand experience. Santana thinks of Danza Azteca as a “puerta” — a door — that opens one up to exploring more about their indigeneity.

“When you’re doing [Danza Azteca], you’re involved in a process of reclamation, restoration, reinvention and reconstruction of these practices,” Santana said. “Recreating again, in some ways, as best as we can with as much as we can know.”

Santana thought it was important for him to connect with his own indigeneity, but he also began bringing his family — including his son sophomore Alejandro M. Santana — to NAYA, so that they could also connect with their heritage.

The Santana family also attended Oklahoma’s Muscogee Creek Nation Festival in June, as Santana’s children are citizens of the Muscogee Nation.

This helped A. M. Santana connect with others from his culture, which wasn’t something he had while attending NAYA events as a child.

“We went to a stomp dance, and I had this feeling of euphoria,” A. M. Santana said. “It felt amazing getting to practice something that I’d wanted so badly as a little kid.”

A. M. Santana explains that understanding his heritage helps shape his empathy, like how his father, Santana, felt more rooted in the world after connecting with his heritage.

Santana also incorporates indigenous cultures within the UP community through MEChA, NAA and the Ethnic Studies Club. While these clubs tackle different themes, their focuses overlap in building community between students and the communities they intend to serve beyond UP.

Since MEChA’s recent revival on campus, the group has put on events like Santana’s Mexica metaphysics presentation on Oct. 9. According to Amy Ongiri, director of the ethnic studies program, the event’s turnout demonstrates the demand for ethnic studies on campus.

“I was like, ‘It's the day before break, … who is going to come to this event?’,” Ongiri said. “The event was standing room only, he talked for an hour and a half, and people were riveted.”

Through NAA, Santana has sent students to American Indigenous Business Leaders (AIBL) and Reservation Economic Summit (RES) conferences to cultivate their leadership skills, as well as helped organize UP’s first annual powwow in April.

The overlapping themes of MEChA and NAA reflect the history of the Americas and the indigenous peoples who’ve lived here. Together the clubs can help students who may struggle with balancing their national culture with an indigenous identity.

“I really try to encourage students to look into that and to see themselves as indigenous because for most [Latino] students, that’s probably true,” Santana said. “I encourage students to look into it and not play into the colonized way of thinking, which is to say, ‘That’s not me, I’m Spanish’.”

Santana not only advises the Ethnic Studies Club, but serves as program coordinator for the ethnic studies program, which he helped create with former psychology professor Sarina Saturn in 2021.

Ongiri sees how Santana’s background in philosophy has influenced his work in ethnic studies.

“I would argue he always was doing ethnic studies, but he's really thought more about positioning his own intellectual work within the rubric of ethnic studies,” Ongiri said.

Ethnic studies, like philosophy, deals with widening the lens through which one views the world. Neither field can be studied without diligent effort.

For Santana, reaching this level of effort didn’t happen overnight. Santana assures that connecting with one’s indigenous heritage is often a long process.

“It can be kind of difficult, but it’s very much worth doing,” Santana said.

Editors note: An earlier version of this article was published misstating that Alejandro Santana's mother was from Sierra Juarez instead of Ciudad Juarez.

Kaeden Souki is the Sports Editor for The Beacon, he can be reached at souki28@up.edu.