How do people develop misconceptions about robots? How do ants forage for food? On Oct. 31, UP hosted an undergraduate research symposium where students showcased their work and answered these questions and more.

The symposium featured 39 poster presentations and over 70 students who presented their summer research. Five students across three projects were selected as winners by a majority vote of attendees.

All five students conducted their research through the University of Portland Summer Undergraduate Research Experience (SURE) program. SURE has research opportunities in fields across campus, including chemistry, engineering, physics, math and neuroscience. Students can learn more about summer offerings and when to apply by visiting the undergraduate research page on UP’s website.

Alex Baca, Kailani Maxwell, Dominic Nguyen and Amy Segura, all working in professor Ryan Kenton and professor Christine Weilhoefer’s lab, earned the first two awards. The third winning project was presented by Loren Swaney from professor Laura Dyer’s lab.

Seagrass modulates HABB species in temperate coastal food webs

Senior cell and molecular biomedical science major Alex Baca and senior human biology major Kailani Maxwell presented the first winning project, titled “Seagrass modulates HABB species in temperate coastal food webs.”

The focus of the project is algae, which can be found inside a fish tank or on the top of a lake, and is more amusing than you may think. Algae grows at rapid rates, and as it multiplies, it creates toxins that are harmful to humans and wildlife, classified as harmful algal bacterial blooms (HABB).

These blooms are becoming more common as ocean temperatures rise and become more acidic — the ideal climate for the plant, according to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Over the summer, Baca and Maxwell researched a type of seagrass called “Zostera marina,” or eelgrass. They wanted to know if the amount of eelgrass could impact the quantity of a HABB species called “Pseudo-nitzschia” in a sample of water.

For Baca, this study is important because it can aid researchers in understanding global warming impacts.

“Global warming and industrial activities are harming these seagrass ecosystems, and we're seeking conclusive evidence that these seagrass ecosystems are good to have around,” Baca said. “One [reason is] that [seagrass ecosystems] likely mitigate harmful algal bacterial blooms.”

To do so, the pair tested water in Tillamook and Netarts Bay and compared how much of the HABB species lived in low eelgrass and high eelgrass regions.

Despite a slight correlation between the two, their research did not find enough evidence to support a strong causal relationship between eelgrass and the HABB species.

However, this project did lead the students to ask more questions that will support further research in the lab.

The experience also proved very rewarding for the two students, with Maxwell discovering a new passion for biology research.

“I love doing research so much, [and] the process of discovering new things and trying different methods to see what works and what doesn't,” Maxwell said. “It's like you're a scientific investigator, and it feels really cool. Before summer research, I thought I wanted to be a normal doctor, but now I think I want to do something that involves a lot more research.”

Both students recommend applying for the SURE program, and they especially recommend their lab to any students who enjoyed microbiology classes.

And for any student worried that a lab doesn’t fit into their ten-year plan, Baca has some advice.

“Don't be afraid to go with something that is a little bit outside your field, or [outside] whatever you think you want to do long term,” Baca said. “Because odds are, you'll probably fall in love with it.”

From Bloom to Boom: Domoic Acid as a Potential Growth Stimulant for Pathogenic Vibrio Species

Dominic Nguyen and Amy Segura earned the second project win for their research titled “From Bloom to Boom: Domoic Acid as a Potential Growth Stimulant for Pathogenic Vibrio Species.”

This project focuses on the same algae from the previous project, Pseudo-nitzschia, and the specific harmful toxin it produces, called domoic acid. The goal of the study was to understand how domoic acid may influence the growth of another harmful bacterium called “Vibrio.”

The students' research found that domoic acid had a different impact depending on the type of Vibrio bacteria used. In some cases, domoic acid seemed to act as a stressor for the Vibrio, and in others, as a possible source of Vibrio growth.

In addition to their recognition at the research symposium, the duo’s work also won them the top poster prize for microbiology at the recent Murdock College Science Research Conference.

To Nguyen, the most rewarding part of the research process has been the interpersonal skills gained during the work.

“We get valuable opportunities to talk to other researchers to help them understand [our work], even if they're not from the same field as us,” Nguyen said.

Nguyen also had the unique experience of being hired to this lab as a first-year student. After several years in the lab, he has grown to see why it is so special.

“I really enjoy working under [professor Kenton] in particular,” Nguyen said. “He's always given us an opportunity to design experiments and [project manage] on our own. I wouldn't say he's hands off, but he gives us a chance to redesign experiments ourselves, and [consider] troubleshooting protocols. It helps you think like a researcher or an actual biologist, not just somebody who ‘does biology.’”

For those looking to get involved in research, Segura recommends this lab to students who are curious, driven and flexible.

“Sometimes data or an experiment may not go your way,” Segura said. “You have to learn to adapt. Or sometimes you mess up — I've definitely messed up while doing experiments before — and it's okay. [But] how do you make sure [you] learn from that mistake?”

Coronary smooth muscle proliferation is independent of shear stress

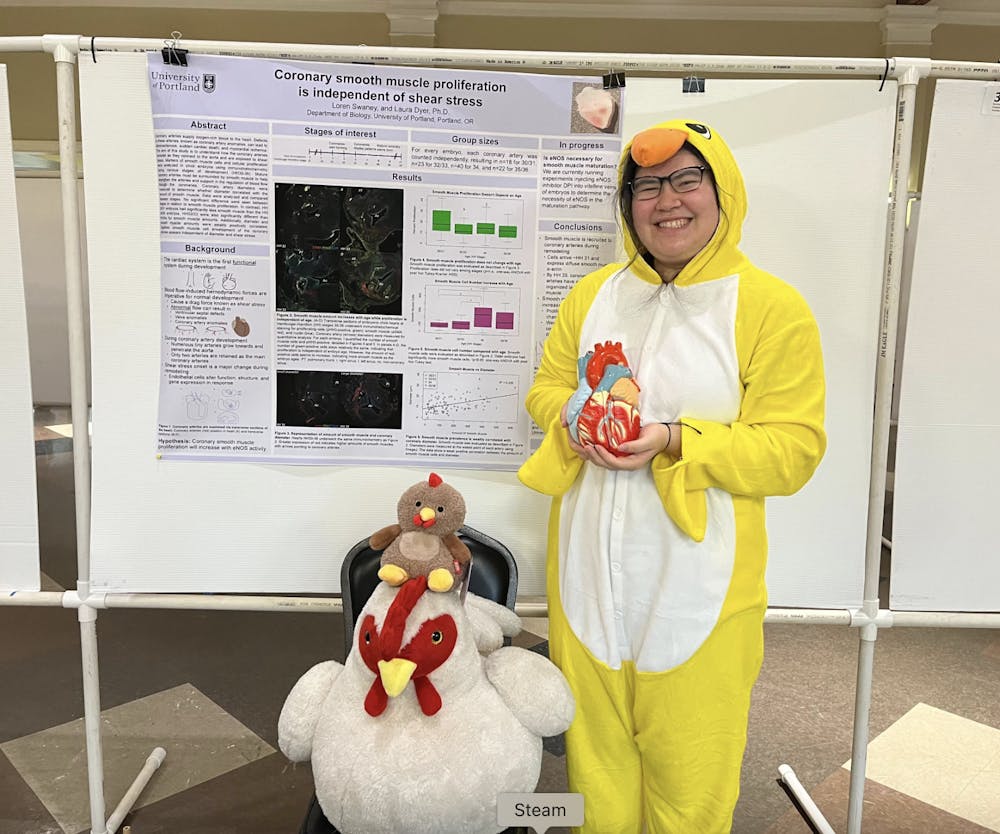

Loren Swaney presented the third winning poster, titled “Coronary smooth muscle proliferation is independent of shear stress.”

The general focus of professor Dyer’s lab, where Swaney works, is how coronary arteries develop. Coronary arteries are the blood vessels that wrap around the heart, providing the muscle with oxygen-rich blood.

The lab hypothesizes that coronaries develop due to a mechanical force called shear stress. Shear stress in the heart is caused by blood as it flows through a vessel. As the blood rushes through the vessel, it pushes up against it.

The scientists working in the lab believe this stress helps develop arteries. To learn more about coronary development, the lab examines how chicken embryos form.

Swaney’s focus was smooth muscle, which surrounds and supports blood vessels. She wanted to understand if there was a relationship between age, smooth muscle development and shear stress. Swaney began her lab as a first-year and was able to finish her project this past summer.

Swaney’s research concluded there was no direct relationship between age and an increase in smooth muscle. This means smooth muscle growth does not cause blood vessel development. However, she and her professor came across other findings in the process.

The lab found that smooth muscle growth is independent of shear stress, meaning that smooth muscle growth does not cause coronary development. They also found that as coronaries grew, the amount of smooth muscle did too.

Swaney has found her time in the lab to be rewarding, and one of her favorite parts is getting to share her work with her peers.

“Part of what's really fun about research is figuring out how to adjust what you're saying to meet the knowledge level of who you're presenting to,” Swaney said. “If I'm presenting to a bunch of developmental biologists, I can be more technical with what I'm saying, but if I'm talking to [a] math person, then [I] have to figure out how to say the science without it sounding ‘sciencey.’”

Professor Dryer’s lab only hires one first-year student per year to commit to working for the lab through their senior year. Because of this, Swaney recommends the lab to anyone willing to commit to the time period.

“Definitely anyone interested in developmental biology, [but also] people who want to learn more,” Swaney said. “Any research is good research.”

Nandita Kumar is a reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at kumarn27@up.edu.