A shift is taking place in classrooms across the nation.

In 2025 alone, 22 states established laws or policies requiring public school boards to limit or ban cellphone use in K-12 classrooms.

Locally, Portland Public Schools (PPS) adopted a policy requiring students to turn off all personal electronic devices during the school day in January of this year.

In July, Oregon banned cellphone use completely during the school day through an executive order signed by Gov. Tina Kotek. The order requires public schools to adopt new cellphone policies by Oct. 31.

As school districts across the state work to adopt policies by the deadline, many of UP’s student teachers are facing phone-free classrooms for the first time.

Senior secondary education and English double major Alyssa Gonzalez, who student teaches at Conestoga Middle School, says it’s been easier to “juggle” classroom management and teaching without phones. But she also finds herself managing students’ negative feelings towards the ban.

“It’s just more helpful to be without phones, especially because we're just now learning how to run the classroom,” Gonzalez said. “But the shift to students going without their phones is something that we're still trying to navigate. … I think they still don't grasp the fact that this is kind of for your own good, in a way.”

Artwork in Beaumont's classroom at Grant High School.

It turns out what may be good for students might also be good for student teachers.

Claire Beaumont, a senior secondary education and English double major, taught at Astor K-8 before PPS’ ban. At the time, Astor teachers could remind students to put their phones away but couldn’t confiscate them, which created a tension that left Beaumont and her supervising teacher feeling “powerless.”

Following PPS’ unilateral ban on cellphones, Beaumont taught at Roosevelt High School where she experienced a “huge increase” in student engagement after the change. Beaumont says she was able to spend less time policing electronics and more time connecting with her students.

“I still give them reminders to stay on task, but I can also ask them questions like, ‘Oh, how's your day going? What are you working on right now?’ instead of just having their only impression of me be that I'm the person who asks them to put their phones away,” Beaumont said.

Niall Sexton, a junior secondary education and English double major, also finds the phone restrictions to help increase student engagement.

Sexton’s first placement after the PPS ban was at Ockley Green Middle School which used Yondr pouches to lock phones away — a factor he thinks has improved the student teaching experience.

“It was way easier to lead a lesson when you're not trying to fight for kids' attention,” Sexton said. “I think it might be helpful for UP education students to be able to get more attention from their students. And I think it'll make the student teaching process a little bit easier.”

A Yondr phone pouch. Pouches are used in some Oregon schools to restrict student cellphone use.

Not every UP student teacher is adjusting to the phone ban, however. Many of them work in local private schools that have longstanding no-phone policies.

Senior secondary education and English double major Sandra Padilla Cervantes has taught at St. Mary’s Academy and De La Salle North Catholic High School, two schools which prohibit cellphone use in the classroom, according to their respective student handbooks.

While Padilla Cervantes hasn’t had to adjust to the ban, she says her biggest worry with the change in public schools is how students will manage free access to technology in college if they can’t practice that skill in high school.

“My biggest concern is sending kids off to college, right? And they have their phones with them,” Padilla Cervantes said. “We're not teaching kids to be coexisting with their phones. We're just putting like a temporary solution, but that's not going to help them when they're in college.”

Gonzalez also shares some concerns with the ban. She sympathizes with students who aren’t distracted by their devices but feel more comfortable having them, or those who want to communicate more with their parents.

Eric Anctil, a professor of media and technology whose work focuses on human engagement with technology, says that though some might have concerns with the ban, the verdict’s in on cellphones in schools: there should be less of them.

“I can't think of how you put together an argument that this [ban] isn't good,” Anctil said. “I can't think of any data that suggests it isn't good. I can't think of anyone out there advocating that there should be more phones in schools. To me, that's pretty strong evidence.”

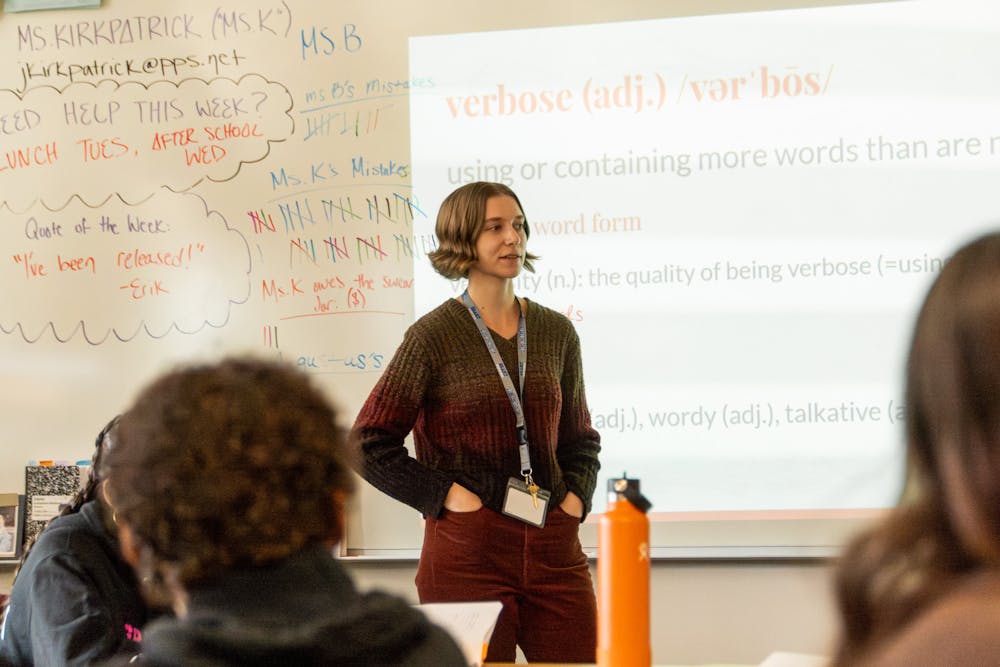

Beaumont teaches at Grant High School.

Anctil says that phones pose a problem in schools because they take students out of social spaces — a physical or virtual place where people interact — like classrooms and into online spaces that distract from learning.

“If you're in a classroom and you're constantly opening your phone because you're in some sort of … Snapchat war with somebody,” Anctil said. “If you're in that social space, you're not in the social space of social studies, you're not in the social space of calculus class. You're arguing with somebody through a messaging app. That's really where you are.”

When phones are taken out of the equation, the student is dropped back into the social space of the classroom, which allows them to focus on and participate in their learning, according to Anctil.

Anctil, who has previously consulted on student technology use for schools, says he’s spoken to principals and teachers who love the ban, students who hate the ban and some students who are “okay” with it because it gives them “permission to disengage.”

Sexton says his support for the policy comes in part from looking back with a similar sentiment on his childhood.

“When I was that age, I was on my phone the whole time,” Sexton said. “I think it's good [to have] time for them to count on not having their phone so they can figure out what it's like to be human without a phone there all the time, which I think is important.”

Maggie Dapp is the News and Managing Editor at The Beacon. She can be reached at dapp26@up.edu.