As one of the first yakitori grills in America, Tanuki restaurant of Portland was renowned for its association with iconic restaurateur Michael Vidor. But, Tanuki was also famous for its chairs.

In 1979, Robert “Bob” Shimabukuro designed the restaurant’s rustic decor and later served as part-time chef and co-owner of the establishment.

“[Shimabukuro] actually built the restaurant, Tanuki,” Director of Collections and Exhibitions at the Japanese American Museum of Oregon (JAMO) Lucy Capehart said. “He built the whole interior and then he was the main chef, too. [...] It was a restaurant that he owned jointly with Michael Vidor. There’s not a lot left unfortunately there’s no menus or anything. I wish there was.”

Known for more than just his work at Tanuki restaurant, or even his sentimental woodworking, Shimabukuro was also a civil rights activist and proponent of the Japanese American redress movement. This movement sought to bring Japanese Americans reparations for their detainment and incarceration during World War II.

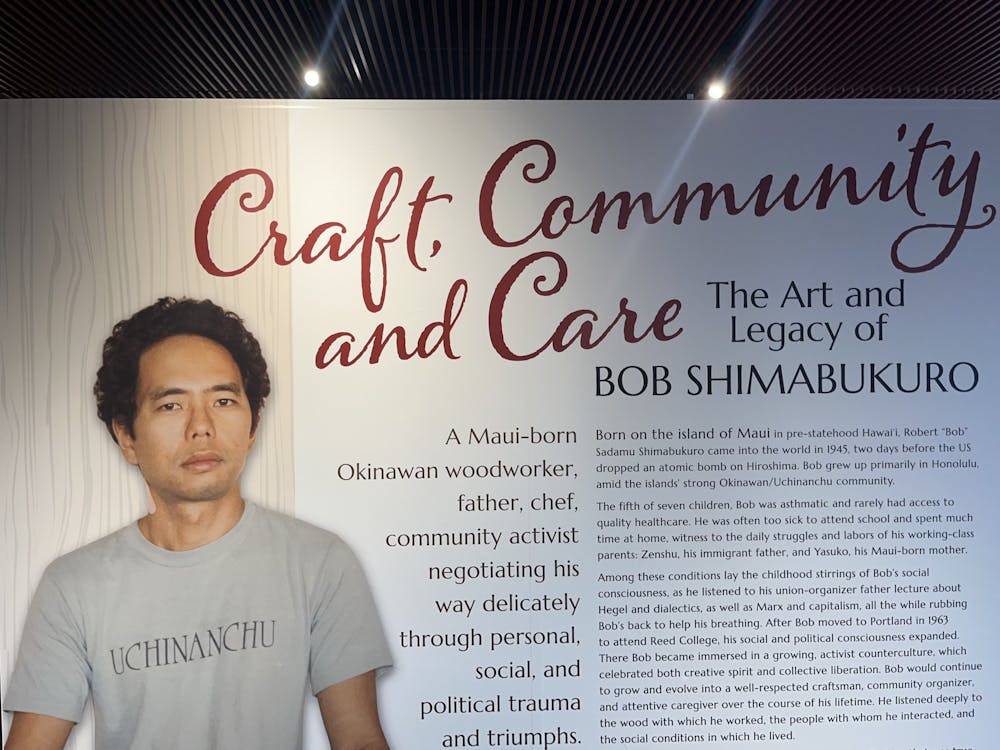

Called “Craft, Community, and Care: The Art and Legacy of Bob Shimabukuro,” the JAMO exhibit held from Feb. 17 to April 14 sought to uplift Shimabukuro’s life of activism — from his work regarding anti-Okinawan discrimination to the AIDS epidemic.

“[JAMO] thought he was a very talented, thoughtful, progressive leader that should get recognition,” Capehart said. “He lived his life according to his principles or his beliefs. [...] He was very involved in the fight against AIDS in Seattle and he was a writer who worked for ‘Pacific Citizen’ in California and ‘The International Examiner’ in Seattle. He expressed a lot of opinions that way. He was a remarkable guy who unfortunately passed away [in 2021].”

JAMO is nestled on the corner of NW Flanders Street and Fourth Avenue in the heart of what was once a vibrant Japantown.

A ten-minute walk from my dorm, the 35 bus-line was a straight $2.80 ride to the museum.

Someone manning the entrance unlocked the door for me to enter, where I soon walked into the museum’s gift shop full of tabi socks and handmade jewelry. The room was small, and I walked past visitors purchasing souvenirs on my way to the exhibit. Shimabukuro’s face greeted me as I entered.

Printed on a panel, he wore a shirt that read “Uchinanchu,” a reference to the Okinawan diaspora. Alongside this photograph, blocks of text detailing Shimabukuro’s childhood in Honolulu revealed his struggles with asthma and poverty.

Going into the exhibit, I expected that Japanese American community and redress would be at the forefront, but I hadn’t anticipated the music stand to my right in the room.

Shimabukuro wasn’t a famed musician. He was a woodworker, and made the piece — along with a toilet seat — for his brother-in-law, according to the exhibit.

“I was interested in his woodworking, especially because of his incredible artistry,” Capehart said. “A lot of the pieces are made specifically for individuals, he doesn’t just make furniture. He always had a purpose to make a piece of furniture for [someone]. He made a small chair for his second wife, Alice Ito, a rocking chair just to fit her.”

After his graduation from Reed College, Shimabukuro apprenticed at the North Portland St. John Furniture Trust, according to the exhibit.

“Some of his woodworker friends who came through [...] were saying he was really funny and the smartest person they ever knew,” Capehart said.

As I weaved in between displays of furniture, family portraits where children outweighed the adults greeted me at every turn. A plaque on the side of one panel acknowledged the people who made the exhibit possible. Friends and family, including Shimabukuro’s daughter, were credited for their participation.

“The family was very much a part of this exhibit,” Capehart said. “We worked with them very closely and they had many connections and knew everyone who had furniture, basically so they could help us borrow things from individuals [because] people trusted them. Something that a community museum like us can do, whereas other museums can’t, we work with actual members of the community to create exhibits. [Shimabukuro’s family] was definitely a part of that.”

Shimabukuro’s close friends and relatives shaped the exhibit, and his family equally defined his life story. Growing up with a union-organizer as a father, Shimabukuro’s activism flourished from a young age.

“I thought about dad now,” an excerpt from an unpublished Shimabukuro work at the exhibit said. “Wondering what he had wanted from me. Hegel. Marx. Engels. All of these guys popped into my mind. I remembered his humor, his political analysis, his off-beat interpretations of events which surrounded his life. It had been obvious that he wanted to pass on something.”

Other pieces of Shimabukuro’s writing followed me as I moved through the room. His activism would further sprout within his journalism, where Shimabukuro wrote extensively on the redress movement and his Okinawan identity.

“AJAs (Americans of Japanese Ancestry) often said (derisively) about the Okinawans in Hawai’i, ‘the difference between a Japanese and an Okinawan is that the Okinawans aren’t afraid to make an ass of themselves,’” Shimabukuro’s 2016 “International Examiner” column said. “Given my initial impressions at Reed, I decided I could take that as a compliment and survive very well. As a Reed Student. As an Okinawan. And I did.”

After his time writing for national Japanese American newspaper “Pacific Citizen,” Shimabukuro moved to Seattle and later co-founded the Asian Pacific AIDS Council in the wake of his brother’s death.

Underneath a glass partition, I saw that Shimabukuro’s zine, “Snapshots of Actual Reality: A Salute to a Brother with AIDS,” was on display near his book about Japanese American redress titled “Born in Seattle.”

“His book ‘Born in Seattle’ really goes through his actions and participation in the redress movement, which I think people should realize was a coming together of many, many people who tried to make reparations happen,” Capehart said. “It took a tremendous effort because [...] [people] had to really rally. That book explains a lot of it.”

Remnants of the redress movement also decorated the exhibit walls, including a scanned Day of Remembrance flier.

“Remember the concentration camps / stand for redress with your family,” the flier said.

Japanese American redress remained an important theme as I left the Shimabukuro exhibit to explore the rest of the museum.

Small details, like a replica of a shattered window, depicted the violence Japanese American businesses underwent during the 20th century. Another display illustrated the bedroom of an incarcerated Japanese American. Fly traps filled with fake bugs showed the unlivable conditions many faced during detainment.

“I’ve been appreciating it’s a very approachable museum,” J. Kelley, a first-time visitor of the museum, said. “There’s a robustness to the content but it's not so much that you're getting lost in it. I like to read and take in everything, and this feels [...] manageable.”

UP’s Japanese Student Association (JSA) last visited JAMO in 2022. For Co-President Lannie Hisashima, these visits were an important way to connect JSA to the greater Japanese American community in Portland.

“[JSA asked themselves] what we can do to engage in Japanese culture that isn’t stuck in our little North Portland area,” Hisashima said. “Once we knew that there was a museum that showed the history of the [Japanese American] experience, that’s not a common thing, it was like, ‘Oh my God, this is an opportunity to take everyone out on this trip.’”

As I toured the remainder of the museum — including a library room, a WWII Nisei soldiers’ exhibit, and Minoru Yasui’s prison cell exhibit — the parts which stood out to me most were the museum’s interactive elements.

A board of moveable pieces defining the different Japanese American generations called me “Nisei,” or a second-generation Japanese American.

Near the museum exit — which would loop back to the beginning for me to once more walk through Shimabukuro’s exhibit — was a desk with paper and pens.

I took a piece of paper for the prompt “what will your part be?” referring to JAMO’s dedication to ensuring the survival of democracy to prevent future instances of discrimination.

I hung my answer on one of the wooden rods stuck to the wall nearest me — dangling my paper amongst many other scraps.

Walking back through Shimabukuro’s room towards the museum exit, I lingered once more at my favorite piece of his woodworking: “Box for Chisao.”

“As [Shimabukuro] became active in Portland’s Japanese American community, he grew close to other organizers, like Peggy Nagae and Chisao Hata,” the exhibit said. “For Hata, whose children were Black and Japanese, he made a box out of Padouk, a tree that grows in both Africa and Asia.”

At first glance, the box might come across as nothing more than a piece of art. But, Hata’s box also reveals Shimabukuro’s contributions to Portland’s Japanese American community. Today, we are left with his newspaper clippings, stories from the now-closed Tanuki restaurant and a long legacy of activism.

JAMO’s next exhibit starts May 4 and is about Portland businessman William Sumio Naito. The museum is open Wednesday through Sunday with a $5 student discount. First Sundays of the month have free entry for all.

Camille Kuroiwa-Lewis is a reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at kuroiwal26@up.edu.