On March 18, UP connections invited Gabby Rivera, an author, storyteller and advocate for the QTPOC (Queer, Trans, and People of Color) community, to be the keynote speaker for their Women’s History Month event. Rivera gave an inspirational presentation about how she encourages people of all backgrounds to create and daydream through her work.

“I am a writer, I am a queer Puerto Rican comic creator from the Bronx and I'm also a deep believer in the power of joy as action,” Rivera said.

Rivera is the first Latina to write for Marvel comics, penning the series “America” which is about the latest superhero to enter the Marvel Universe, America Chavez, a 19-year old Latinx girl with the ability to punch through different portals and venture through different dimensions.

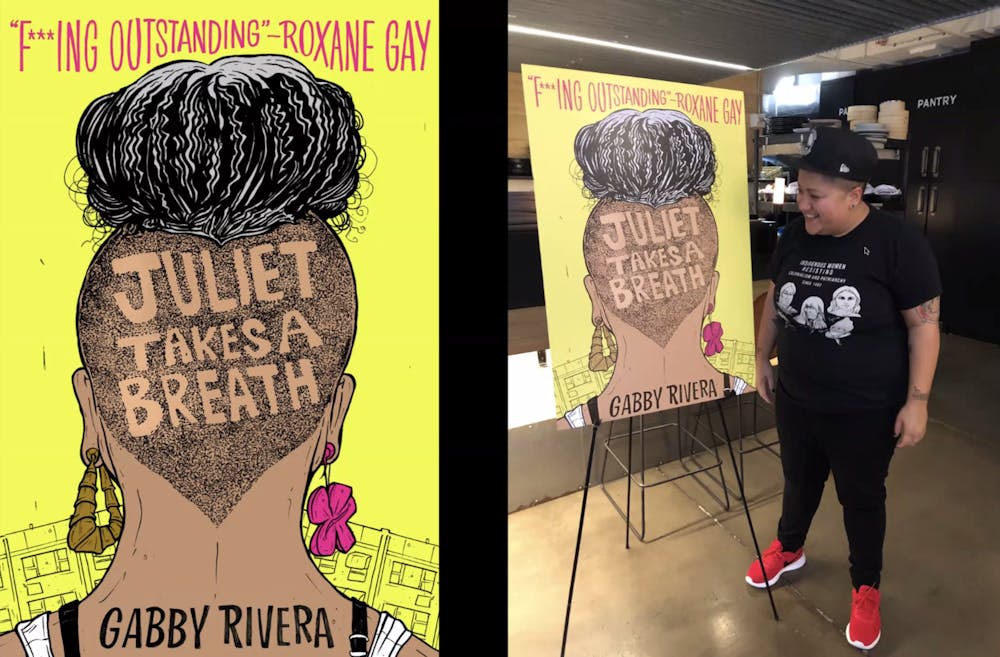

Before writing for Marvel, Rivera wrote a critically acclaimed debut novel called “Juliet Takes a Breath”, a story following a young woman leaving her home in the Bronx to the whitest city in the country, Portland, Oregon to work for her favorite author. Through the novel, she has to learn how to navigate through her life being a Puerto Rican lesbian. It showcases the intersectionality between ethnicity and sexuality.

Gabby Rivera seeing her book as art for the first time.

Screen Capture by Brie Haro

Through the event, Rivera spoke passionately about why she chooses to write in the contexts of her own communities and how it affects the way those communities look at themselves, when the mainstream media typically tries to exclude them from the narrative.

Below are the highlights from the event:

Queerness:

“At first my queerness was something that I didn't understand, I didn't ask for and I didn't want, I didn't have the words for it. It wasn't like at 11 years old, [I could say] ‘Oh, this is my queerness and my gender presentation.’ I didn't have those words. I grew up in the ’90s and you were lucky if the dictionary had [the word] Lesbian. I had no words for gender dysphoria, I had no words for wanting to come out...I didn't have anything I just had my silence.”

Most representation of Queer love has only shown the struggle, and while she doesn't want to discredit the struggle that has occurred, she wants to try and share the joy that is often overlooked.

Screen Capture by Brie Haro

“Now, as a 38-year-old human being who is healing right and wanting to offer as much healing, as I can in my work, I see my queerness as this blessing, as this protective sunlight that the universe has bestowed upon me, because they knew the tough [experiences, it was like] the ancestors knew, [and said] ‘Oh this world isn't ready so let's make her queer so that she can change the world around her effortlessly.”

“Your family [and] your relatives have to go on their own journey [of your understanding queerness], and that is not your work as much as you probably feel like it is. Your work is to heal, to love yourself, to find all the things that you need to say and say them when it feels right, but your job is not to meet anybody's hand through your queerness.”

Being Latinx:

“I used to identify solely as Latina, and, and now I'm realizing and learning, right, that that is just a term to categorize a group of people.”

“Growing up in a Puerto Rican household, you're expected to like look a certain way and behave a certain way, and cater to the men and the boys in your life, and even as a little kid I just didn't fit.”

“With that word Latinx, if we claim it, we also have to explore how it is harmful and how often it erases black indigenous folks and Afro-Latinos, There is so much complexity there. That word also reminds me that first and foremost, I'm Puerto Rican and my energy, my love, and my spirit come from my grandmother. It comes from the island of Boricua, so I hold it all very close and I'm always wondering, ‘what else can I learn about this part of me?’”

Joy as action:

“We live all these intersectional lives…[where] sometimes, always feels like it hurts. Everything hurts sometimes, that's why I hold on to joy very deeply and very firmly because even in the hardest moments, there is a way to unlock that ancestral joy and revel in someone else's joy and let it surround you.”

“Joy reminds us, reminds people of color, and reminds queer people that we are allowed to be joyful. We are allowed to celebrate as much as we talk about ancestral trauma and we must talk about and revel in our ancestral triumph.”

Gabby Rivera (left) and Yuri Hernandez Osorio (right).

Screen Capture by Brie Haro

“Even when the United States was ransacking [my grandmother’s] island, even when the United States was telling them that it was illegal to be Puerto Rican, to waive Puerto Rican flags, and to speak Spanish, on their own island. Even when the U.S. taxed, gentrified, and sucked up the land and resources from their islands. They still believed in the American dream. That's some kind of joy, that's some kind of deep-rooted ‘we will hold on to ourselves’, at all costs.”

Pulling inspiration from her roots:

“My grandma Carla worked so hard, she worked in sweatshops, she worked in places that had no ventilation with dyes that weren’t regulated and would burn her skin. She worked so hard that at 54 she passed away from cancer that had developed from those dyes from that lack of ventilation. And I think about what happened to her American dream.”

Joy was the main factor in how Gabby Rivera feels her Grandmother must have been able to work as hard as she did, to reach the light at the end of the tunnel.

Screen Capture by Brie Haro

“My other grandma, who was a little more able to assimilate into what white Americans considered acceptable, so she changed her name from Amalia to Emily. She worked her way up from a washerwoman to a woman with a master's in education. She was a homeowner, and she lived long enough to see me graduate from college. All the ways that she was able to flourish is incredible given where she comes from what she started with...and she passed that on to me.”

How her writing career started:

“When I'm here writing these stories and trying to figure out myself in my place and how I can interact and connect with my communities, I Think of my grandmothers. I think of how they both believed in this country so much, and they both believed so deeply in the American dream.”

“The 90s were terrible for LGBTQ representation right, not only were we fighting a pandemic then, and all the gay people were told ‘You are going to get HIV and pass away’ That was a real fear. I didn't know if I would survive my life and I didn't know if I would survive s a queer person. They told us that we wouldn't they hoped we wouldn't.”

“I don't care about white writer societies or mainstream or anything like that. We're going to be dikes, we're going to be queers, we're going to be in love, we're going to be happy, and we're going to live triumphantly to the end of our books and our movies, and that’s “Juliet Takes a Breath’.”

Working on America Chavez:

When discussing America's tragic past, Rivera wanted to show that people heal with joy rather than dwell and become undone. "When everything is painful you have the right to sit in the sun and heal."

Screen Capture by Brie Haro

“I wanted America Chavez to be like a safe and gentle place where people, especially young people of color, could pick up the comic, and be like, ‘Oh I feel loved, I feel cared for, I don't feel stressed’ I don't want to create art that harms, my people and my communities.”

“Marvel Comics came to me, and I say that like with pride and also humbly because we have been taught that we have to chase after, bust open these rooms, demand a seat at the table. You can do all that, but then there are times where I say ‘No, I do what I do, I believe in what I do, and if you want to work with me then come make it happen and Marvel showed up.”

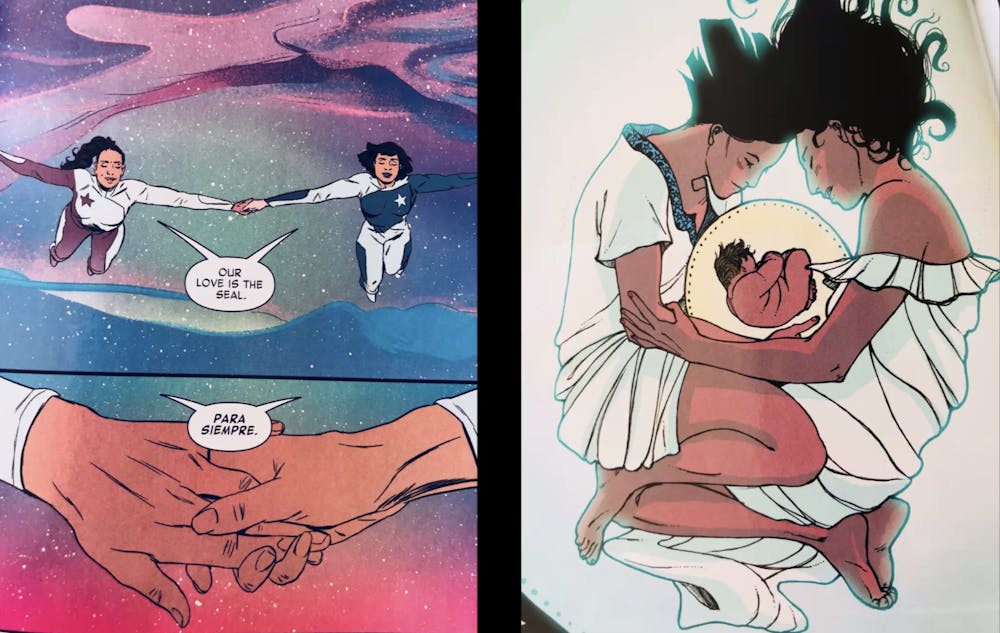

America Chavez has two moms who's love was so powerful that they were able to manifest life.

Screen Capture by Brie Haro

“They already had America Chavez she was already Latina, she was already queer, she was already so strong.”

“in my head [I wondered] what it looks like to be Latinx in outer space, intergalactically. If you're white, in outer space, they don't necessarily have to tie you to Kentucky, you know what I mean? For a lot of folks that's obviously not enough because if Latinx isn't an identity, then does that mean she's nothing in outer space? You can't assume that everyone who's brown, beige or likes rice and beans is Latinx, it's complicated.”

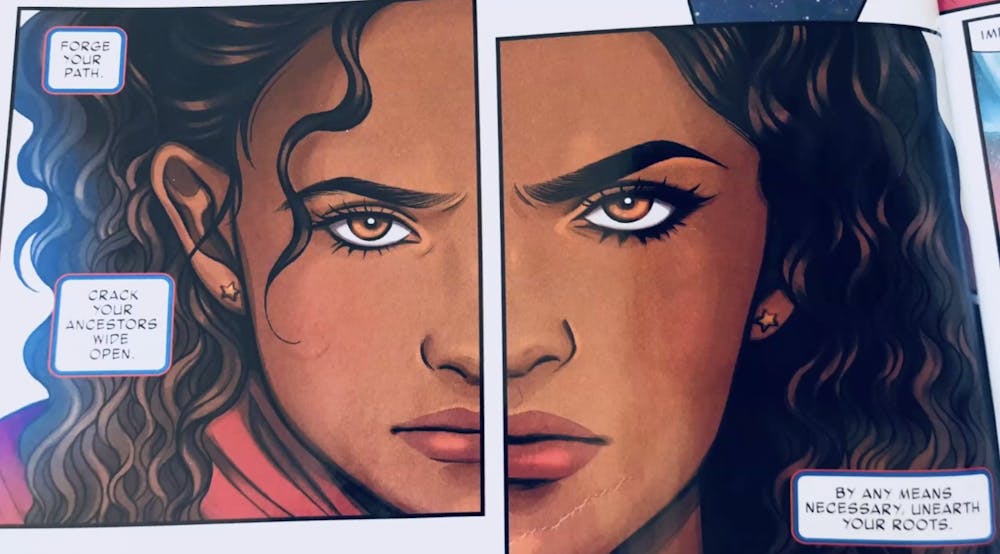

5 (left) and 19 (Right) year-old America Chavez, reflecting on who she has become and what has contributed to her growth.

Screen Capture by Brie Haro

“And imagine [what it’s like] for our Muslim brothers and sisters out there when they put a travel ban on you, for our undocumented brothers and sisters and non-binary family right and gender-fluid magic humans...When they [United States] make you show papers as if you don't belong everywhere just because you exist. Here is a superhero that makes her own way, she punches through all of that.”

“On the left is 5-year-old America, and on the right is like 19-year-old America, there is language here that says ‘Forge your path, crack your ancestors wide open, by any means necessary un-earth your roots.’ That is intentional, that is an offering to queer kids of color saying ‘Yes go. You have ancestors. People have been here before you are not alone. You have every right to find and to learn about who you are at your own pace on your own time.’”

“With America having gay moms I was like ‘Let's do something wild, let's create a birth scene where the love of two intergalactic women is enough to manifest new life.’ [And through that] we get to reimagine and find joy in these places where normally there is exclusion, where normally we [the LGBTQ+ community] are pushed out. Even now, as far as we've come, a lot of folks want to push queer people and trans people out of the birth narratives, and i just don't have time for that. There's so much love to be shared, why not just share it.”

The writers didn't have to make up these kinds of narratives with white men because they had real life experiences to draw from.

Screen Capture by Brie Haro

“There's this moment here, and as you can see the real villains in this novel are just like those same white dudes [referring to white supremacists in Charlottesville]. I didn't have to make this up, it was just me trying to grapple with what I see all around me, and the ways that they [white men] present themselves as aggressive and violent towards us.”

“I want to provide a safer space, but I also want to write something that is present and holds this kind of violence, accountable, and says that your rage, as a kid of color, as a black person, as a disabled person, and as an Asian American person, your rage is so necessary and important. You're allowed to be pissed and you must rally. We must come together, we are allowed to stand up for each other, and we must.”

“In this moment I just wanted to offer peace of mind to all the kids, all the brown women, all the black women, and all the Black and Brown and non-binary folks. To everybody who in any way can connect with this character, offer peace and the right to sit in the sun. You do not have to keep up with capitalism, you do not have to keep up with a routine that doesn't serve you, or doesn't serve your joy. And when everything is painful, you still have the right to sit in the sun

and heal.”

Brie Haro is a Reporter for The Beacon and can be reached at haro23@up.edu.