In early May, the previously-buzzing Bluff suddenly vacated. Students finished their finals and left campus in droves. Some headed home for much needed rest and relaxation; others went abroad with fellow UP students; and still, others played house in the University Park neighborhood.

Four months of summer jobs, internships and hobbies later, summer activities are reduced only to the topics of awkward icebreakers on the first day of class. Even outside The Bluff, however, UP students are constantly striving for new experiences. The Beacon spoke to seven students about their summers — from St. John’s treat trucks to uncovering tombs in Spain.

Katie Norris (left) and Sam Rivas recline during a rare break. Photo courtesy of Katie Norris.

Katie Norris and Sam Rivas

For most people, playing in the dirt is a summertime activity that will eventually be replaced by new, much less interesting obligations. Others hit a streak of luck — with hard work.

This summer, senior biology major Katie Norris and senior math major Sam Rivas travelled to the Spanish island of Majorca through the Pollentia Undergraduate Research Expedition (PURE). They spent late June to late July excavating tombs in the cemetery of the city to gather research on bone and pigment analysis.

Sam Rivas holds an intact human skull. Photo courtesy of Katie Norris.

Rivas and Norris worked alongside five other UP students, students from the University of Barcelona and several UP professors, including Professor Ronda Bard of the chemistry department. In the four weeks they were there, they spent 160 hours digging tombs and painstakingly excavating human remains and artifacts, some of which dated back to 500 B.C.

Norris and Rivas themselves found two tombs that hadn’t been touched by previous excavators. They believe the tomb was from the first century B.C., and hadn’t been touched in more than 3,000 years. Inside, they found the bodies of a child and a mother, still in complete anatomical form.

It was moments like these that Norris and Rivas will remember. They also recalled finding a perfectly intact human skull from the Roman period.

“I don’t even know how you would describe that,” Norris said.

“You can’t,” Rivas chimed in. “When I first saw it, I was in a group of people. And the minute you pull it out everyone stops talking. It’s just silence.”

Most skeletons excavated had already been disheveled by treasure hunters. This rare skeleton was discovered in perfect anatomical form. Photo courtesy of Katie Norris.

Despite working long hours — morning through afternoon in high temperatures bent over tombs — Rivas and Norris still found ways to explore the culture and city around them. In their rare free days, they went cliff jumping, climbing, snorkeling and paragliding around the island. One weekend, they rented a moped for a chaotic trip around the island.

“It’s a lot harder than it looks,” Rivas said, laughing.

In the culmination of their research, the city held an “open house” of the cemetery, inviting all citizens to see the excavated tombs, artifacts and remains. Rivas and Norris both took note of their increased reverence for Spanish culture and history.

“You definitely gain a different type of respect when you’re digging up bodies,” Norris said.

Junior Zachary Sessa spent his summer as a legal intern at the non-profit Workers Defense Project.

Zachary Sessa

Junior Zachary Sessa spent his summer as a worker’s right’s advocate at the non-profit Workers Defense Project in Austin, Texas. Sessa served on a legal team focused on advocating for fair wages, proper safety and training in the construction industry, and combating the exploitation of disadvantaged workers.

The organization, which required Sessa to speak Spanish as well as English, used a holistic blend of legal clinics and education, even offering English classes to their clients.

Sessa and his fellow interns. Photo courtesy of Zachary Sessa.

In Texas, where one construction worker was killed every three days in 2017, employers are not required to subscribe to worker’s compensation. Sessa said the majority of cases brought to them were wage theft, targeting workers who would devote weeks to a construction project and not be paid for their labor. With the proper alignment of many legal moving parts, the laborers might receive their income. Other cases didn’t match the criteria.

“It was so frustrating to know that this worker used their hands in the heat of Texas for two weeks, building something for this multimillion dollar developer, and then they’re not paid at all for the work they did,” Sessa said. “That was probably the biggest thing I had to learn — that you can’t help everyone.”

As a Spanish and social work double major with a political science minor, Sessa said that this experience would provide more context to the classroom and his future endeavors. As an Austin native, seeing a legal struggle against exploitation unfold in his backyard provided an extra layer of significance.

The Workers Defense Project is currently calling for deeper structural changes to emanate from Austin nationwide.

“You can have as many millionaires as you want, but if you don’t have the labor to do the actual work, that’s meaningless,” Sessa said. “So, pay workers fairly.”

Madison Thibado (left) poses with her coworkers and a cow skeleton at a work site. Thibado spent her summer interning with Agriculture Research Services. Photo courtesy of Madison Thibado.

Madison Thibado

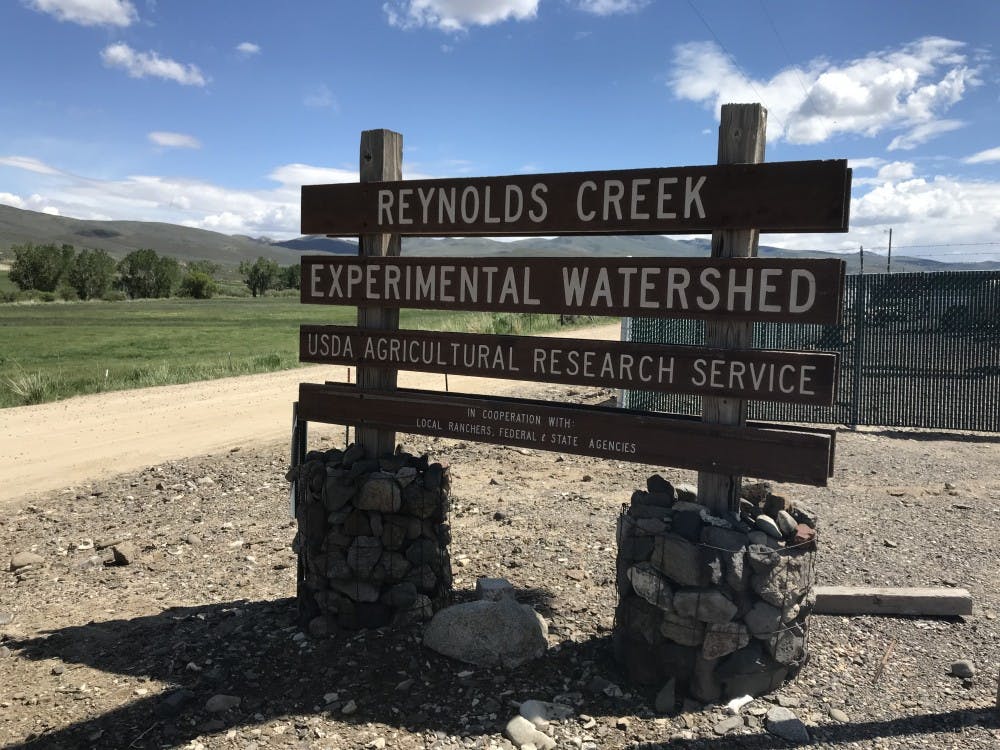

Junior environmental science major Madison Thibado spent her summer working for the Agriculture Research Services as a research support intern. While based out of Boise, Idaho, Thibado spent almost every day at the Reynolds Creek Experimental Watershed, creating a comprehensive data set of venegation — or, as she described it, “counting plants.”

Thibado explained that the Reynolds Creek area is particularly useful to environmental scientists as it contains a multitude of information about climate, water and snow behavior. The data set created over summer is now free to public use, and has been used by an environmental scientist located in Germany to make inferential comparisons of vegetation behavior in the United States and Germany.

Thibado spent most of her time at the Reynolds Creek Experimental Watershed, located in Boise, Idaho. Photo courtesy of Madison Thibado.

Thibado worked long days, typically leaving at 6 a.m. to drive to the work site. This trip involved an hour and a half car ride, then an ATV ride. At the site, she and her team would spend hours using a point frame to establish 3D models of the plot they were surveying.

“I knew I was really interested in doing research before I started this job, but I didn’t really know what I was doing, because I was still a sophomore,” Thibado said. “But then with this job, I got my foot in with the federal government, which is key. And I also got to see what that type of research looks like.”

Thibado's work crew counts plants at the Reynolds Creek Watershed, investigating species abundance. Photo courtesy of Madison Thibado.

Thibado plans on returning to Reynolds Creek next summer. Beyond the research opportunity, she was grateful to be able to pursue her interests within a team of like-minded people.

“I think my favorite part, honestly, was meeting the people,” she said. “I made some really good friends out there. Just being with people who are just as passionate about the environment and biology type of stuff — was really cool.”

Seniors Adam Ketchum (left) and Luke Cleve spent their summer manning the Moontruck for Moonstruck Chocolate in St. John's. Photo courtesy of Luke Cleve.

Luke Cleve and Adam Ketchum

Senior finance major Luke Cleve had been working at the Portland-based establishment Moonstruck Chocolate since his sophomore year, located mainly at the cafe located on NW 23rd. Before the summer of 2019, a retail coordinator approached him to ask if he would want to participate in the launch of a food truck at the corporate location in St. John’s.

Originally, Cleve was scheduled to man the truck with another employee, but that employee left the company. Cleve was told that they needed to replace him, stat.

“I was like, ‘Okay. I know one guy,’” Cleve said.

He called his housemate, senior biology major Adam Ketchum. Ketchum agreed to take the job on the spot. The “Moontruck” launched for business in the corporate location parking lot on June 15th and was open every weekend throughout the summer until Labor Day Weekend.

The truck, which grew in success as the summer went on, served the menu that has brought Moonstruck chocolate notoriety; moon dippers, which are ice cream gelato bars dipped in milk or dark chocolate with a variety of toppings; and beer floats, a gelato bar submerged in Piper’s chocolate porter.

The food industry can be taxing work, particularly in a close-quarters section like a food truck, but Ketchum and Cleve were never too overwhelmed by the proximity.

“We also live across the hall from each other,” Ketchum said. “We’d wake up, see each other, and be like, ‘Okay, we’re gonna work in a truck with each other?’”

They recalled that almost every Sunday morning, a train would pass through the tracks in Cathedral Park. The conductor would disembark and take a pit stop to get ice cream, often using their walkie talkies to take orders from inside the train. Being located in Cathedral Park also surrounded them with the unique culture of Portland, and specifically St. John’s, such as the St. John’s Hip Hop Festival.

“We got to know a lot of St. John’s locals,” Cleve said. “It was fun.”

Sophomore Lauren Tate spent her summer as an environmental tour guide in Ketchikan, Alaska. Photo courtesy of Lauren Tate.

Lauren Tate

Before this summer, sophomore Lauren Tate was a biology major who had never been to Alaska. After working as an environmental tour guide in Ketchikan, Alaska, for the summer, she changed her major to environmental science.

Tate is a native to Boise, Idaho. She found the position through her friend and fellow UP student, Cami Boesch, who had already spent the previous three summers in Ketchikan. Initially, Tate said that she was unsure if she could take the position.

“It was such a big step out of my comfort zone,” Tate said. “But I got used to it really fast. I got used to it in a few days, and then it seemed like I’d been there forever.”

Tate poses with friends and fellow UP students Cami Boesch and Sophia Truempi during a hike to Shelokum Hot Springs. Photo courtesy of Lauren Tate.

Ketchikan is a city of 8,000 people. Every day in the summer, the town would almost triple in size as roughly 17,000 people flooded in from cruise boats, toured the town and the surrounding islands, then left the town before nightfall. During the surge, Tate led tours for Alaska Travel Adventures around Betton Island, a 40 acre land mass outside of Ketchikan that is full of unique Alaskan flora.

Tate said the most surprising thing about Alaska was the climate. For many, Alaska calls to mind images of heavy snow cover and barren landscape. Instead, the area where Tate stayed was a rainforest of lush greenery and constant rain.

“Everywhere was wilderness,” Tate said. “Our backyard was the forest.”

She recalled aspects of Ketchikan that were entirely unique; such as the Summer Solstice, where the sun didn’t set until midnight, and the sky never fell completely black. She also reminisced of her morning commute, a 20-minute boat ride surrounded by humpback whales.

A photo captured at the summit of Dude Mountain, Alaska. Photo courtesy of Lauren Tate.

Guiding is mainly seasonal work, and Tate said she was unsure that she would return to Ketchikan specifically.

“We founded such a community,” Tate said. “It was kind of a weird feeling, because you knew that you would never really see those people again.”

But even after these students have returned to their normal class schedules, their work over the summer continues to remain an influential part of their lives.

“I think I can bring to the classroom a lot more meaning and context,” Sessa said in reference to his legal internship. “I have practical things in real life to apply it to...real stories, real faces.”

Gabi DiPaulo is the Living editor for The Beacon. She can be reached at dipaulo21@up.edu.