As the crowd filed in an almost full Mago Hunt theater last night, “Mad Forest’s” actors were strolling up and down the aisles, welcoming the audience and saying, “Salut” (“hello”), “Bună seară” (“good evening”) and “Multă

I entered the theater with higher expectations and a more critical eye than most audience members because I was born in Romania and came to the United States at age two.

The production did not disappoint. The actors’ knowledge and reasonably good pronunciation of Romanian phrases were only a few components that contributed to the play’s historical and cultural accuracy.

I’ve heard countless accounts of the Romanian Revolution of December 1989 that overthrew and executed communist dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu. The revolution was the defining moment of my parents’ lives as it represented the many freedoms and opportunities they gained with the fall of communism. I would not be in America writing this article if it was not for the revolution.

A bit of context: Romania became a communist country in 1947. In 1965, power transferred to Nicolae Ceauşescu, who made Romania’s government one of the harshest regimes in eastern Europe. People lived in constant fear. Most of them were starving and they didn’t have basic rights, such as voting and freedom of speech.

The play’s three parts highlighted life during communism, the revolution and post-communism in Romania through the eyes of two families: the

The lighting was almost a character in itself, portraying the dim bleak life most Romanians led during communism. A family sat huddled around a few small candles as their father Bogdan recounted how he was interrogated by the Securitate. This hit close to home because people in my family were interrogated and tortured by the Securitate.

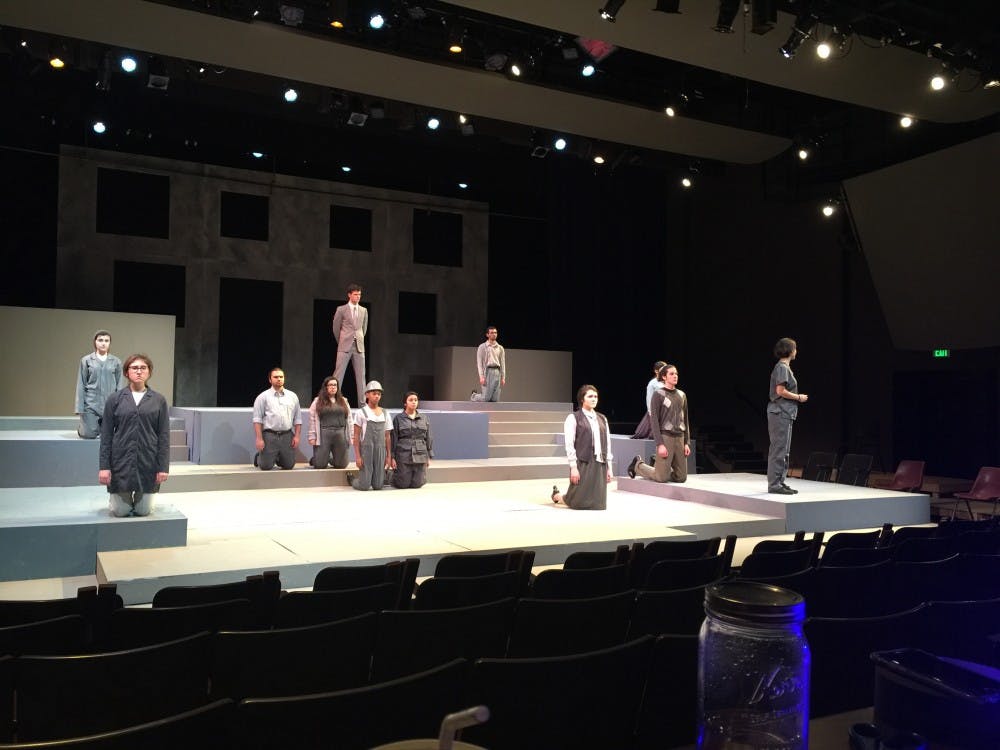

In a later scene, five or six actors stood in line, crouched over and tired in their gray, ugly and shabby clothes—wisely chosen by the department’s costume design crew—effectively conveying the pain felt by people who had to wait hours in line to receive meager rations, hoping they had woken up early enough to get food.

In this moment, Jacob Orr, who played Radu, a young revolutionary, also shouted, “Jos Ceauşescu!” which means “Down with Ceauşescu!” while in line, eliciting gasps and wide eyes from his fellow Romanians, including me.

I doubt the audience grasped the severity of screaming that in public. It’s akin to a child from a strict household telling his grandmother to shut up. It would never happen. You never knew who was a Securitate agent or informant and would eagerly report such a comment.

Though the play approached the heavy topic of communism, there were moments of humor that reflected Romanian culture with the same accuracy. Anybody who has sat through a Romanian wedding knows the agony of hearing the mundane repetitions of the priest and the people he’s marrying.

I felt a sense of gratification as the audience members gained a glimpse of this anguish as they had to sit through the back-and-forth repetition of long religious phrases at a Romanian wedding, delivered in a stoic manner that only I found funny. I snickered as the audience was even forced to repeat “amen” in unison with the actors.

Though the first part was correct in showing the realities of communist Romania, the play can be confusing for an audience unfamiliar with the historical and cultural details.

“I think it’s cool, but I’m pretty confused,” junior Madeline Ochs said.

The second act of the play, focusing on the revolution, was personal and painful. The actors’ accounts of those days were consistent with what my family has told me. It was a time of chaos and panic but also one of hope.

Everyone listened closely as the actors, dressed as workers in dull-colored clothing, explained—some in cracked voices—their fear,

The actors’ passionate performances helped audience members comprehend the human toll of the revolution, in which over 1,000 people died.

“It reminded me it’s just very real,” senior and audience member Ryan Greenberg said. “We hear about it overseas, like ‘seven people died in this revolution,’ but it’s like no, those seven people had brains, and they had dreams, and they had moms and they had their favorite pairs of shoes, and it just humanizes it.”

Except for a bizarre vampire scene the play could have gone without (I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: vampires are not part of Romanian culture), the third scene mirrored the joy and confusion which characterized that era. The actors were overall much happier, shown in the bright lights and their new, brightly-colored clothes. But they also portrayed the anxiety felt by many Romanians.

The turbulence due to this newfound freedom was why director and graduate student Josh Rippy chose to stage “Mad Forest.”

“We don’t grasp what it’s like to go from oppression to freedom—and the things that those people get to decide now and have to decide,” Rippy said. “The choices you have to make when you have freedom and how that affects everything else in your life—that’s important to know, especially in this climate.”

I won’t spoil the end because you should make time in your busy, college student schedule to see “Mad Forest.”

But I will say this: it ends with a toast to the Romanian people and in the most Romanian way it could, a perfect ending to a play that accurately conveyed Romanian culture. Post-communism isn’t perfect, but it’s life—and Romanians always find a reason to celebrate life and enjoy it.