Neighbors cry foul on odors from Daimler Truck North America plant

By Laura Frazier, News Editor frazier13@up.edu

Linda Nakashima complains of a paint smell in the air "so strong you can taste it" near her home on Amherst St. and Wellesley Ave.

Worried about the health of her family, Nakashima, her eyes welling with tears, said the fumes from Daimler Trucks North America, a Swan Island industrial site under fire for pushing pollutants into the North Portland air, dictate if they can go outside. "The smell from Daimler determines what we can do that day," she said. "I'm afraid something terrible will happen to my son for breathing this air."

Neighbor Stacey Schroeder, who lives a quarter-mile from Daimler, said she smells paint most days.

"I have a four-year-old who now on his own can tell me, 'Mom, I smell paint today,'" she said. "I find myself holding my breath as I leave my house."

Philosophy professor Alejandro Santana lives two miles from campus and rides his bike to work. During his ride, he picks up on the Daimler smell, which hangs in the air along Willamette Blvd. east of the main entry to campus and the east side quad.

"I'm trying to get a little exercise in, and then I get this whiff of paint," he said. "It can't be good to be smelling this stuff."

Nakashima, Schroeder and Santanta were three of about 100 people at a public hearing on campus March 7 hosted by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). Neighbors and members of the UP community gathered in Buckley Center to ask questions and share personal testimonies.

Although several Swan Island facilities emit pollutants, the focus has turned to the Daimler Trucks North America Western Star plant on Fathom Ave., where workers paint large trucks, emitting toxic, smelly paint fumes into the air. Daimler, which has 800 employees at the Western Star facility and has been manufacturing trucks there for 43 years, is going through the renewal process for its five-year permit from DEQ.

Neighbors complain about the facility emissions causing headaches and migraines, asthma attacks, nausea and red eyes, and they have had enough of the smell. They're fighting for DEQ to hold Daimler accountable for causing a nuisance odor, but DEQ officials said the agency does not have criteria to regulate the smell.

Neighbors are worried about Daimler's toxic emission levels, but since the DEQ cannot change the emission regulations in the permit process, neighbors are now pushing the agency to regulate the odors.

According to DEQ permit writer Dave Kauth, DEQ cannot change the rules on Daimler's emission levels because rule-making on emission levels is a separate public process unrelated to permit writing.

"We can only put in the permit what is set in the rules," Kauth said. "If something is shown that the levels are set higher than what we allow by rules, we'll make a change."

Kauth said Daimler is within its permit regulations. For example, Daimler's permit allows for the emission of 470 tons per year of volatile organic compounds. In 2012, its facility emitted 187 tons.

However, according to Kauth, Daimler's baseline emission levels, the amount of pollutants it is allowed to emit according to the permit, were set in 1977-78.

Kauth said if Daimler were to go into business today, it's possible it would be subject to more stringent emission restrictions, but not necessarily.

"It's very likely that their actual emissions would be the same," he said. "Total allowed might be less, might be not."

Regulating a "nuisance"

At the hearing, DEQ took questions from the crowd for about an hour. Neighbors shared concerns about how DEQ monitors Daimler's emissions and why the smell is not regulated.

Kauth said Daimler monitors its production and emissions, and DEQ inspects the facility and reviews the annual and semi-annual reports to ensure it is within permit regulations.

According to a statement from Western Star Plant Manager Paul Erdy, Daimler has significantly reduced air pollutant emissions. Over 400 samples have been gathered at the Western Star facility, and a toxicologist helped evalute the data to address health concerns.

"The coatings used at the Western Star Manufacturing facility that have been identified in our sampling are well below established health benchmarks," he said.

Neighbors said even if Daimler is within its permit regulations, its emissions should be regulated as a nuisance odor.

Schroeder said it's obvious the fumes are problematic. She said neighbors have submitted hundreds of odor complaints in the past year.

"We so very strongly feel that daily paint fumes equal nuisance," she said.

Nakashima said she contacted DEQ multiple times to complain about the smell but never got a response.

"We just know they [DEQ] aren't going to do anything," she said.

According to the Daimler permit, the "permittee shall not allow the emission of odorous matter in such a manner as to cause a public nuisance."

But Kauth said DEQ cannot regulate Daimler as a nuisance odor because there is no consistent way to define a nuisance statewide.

"We don't really have a way of saying 'yes they are' or 'no they are not' a nuisance, consistently to where everyone comes up with the same conclusion," he said. "What we want to do is be consistent."

A 2009 memorandum from then - Attorney General John Kroger highlights the difficulty of regulating odors based on whether neighbors consider them a nuisance, even though DEQ has the authority to address odors. The memorandum states that creating the conditions to regulate a nuisance "may be legally difficult to accomplish."

The state has an Environmental Quality Commission to work on air purity standards, but when it comes to enforcing those standards, the subjective nature of smell is problematic. The Attorney General's memorandum states that odor and its effects are "inherently subjective," as is "the relative intensity of the odor."

David Monro, DEQ's Northwest Region Air Quality Manager, said DEQ is serious about developing a nuisance program to focus on regulating odors. But he can't say when the program will be put into place.

"We are moving forward with an aggressive timeline to add that program," he said. "The DEQ is very committed to putting in the time and money."

Erdy said Daimler logs and evaluates odor complaints and has met with neighbors. He underscored Daimler's "commitment to address all concerns that are brought forward to us."

Santana has attended several public meetings with DEQ as well as hosted panels about pollution, but he thinks the agency doesn't have enough financial or staffing support to do its job.

"I think the people at the DEQ are well intentioned," he said. "[But] You get this very palpable sense they can't do very much."

Santana said people expect North Portland to carry the weight. "It's too much that they're asking people of North Portland to deal with," he said. "It's not fair."

Neighbors fed up

Neighbors are not only fed up with what they see as DEQ's apathy towards Daimler, but also with Daimler's refusal to negotiate with them.

Schroeder, a leader of the neighborhood group North Portland Air Quality, said the organization has recently partnered with Neighbors for Clean Air, a citizens group, to continue fighting for better air quality in Portland.

In November 2011, Neighbors for Clean Air reached a voluntary "good neighbor agreement" with Esco, a company operating two steel foundries in Northwest Portland. The agreement was a huge step for air quality advocates.

Schroeder said Neighbors for Clean Air tried to negotiate a legally binding "good neighbor agreement" with Daimler, but the corporation never responded.

"We don't want them to leave and go away," Schroeder said. "What we want is just that they be a good neighbor."

According to Schroeder, the agreement asked Daimler to make a variety of changes, including creating a website to increase transparency and provide an outlet for odor complaints, providing annual public tours of the facility and getting a wind speed and direction monitor to help pinpoint exactly where the smell is coming from.

Schroeder said the most important request the neighborhood group made was that Daimler commit to having a third party analyze its operations and emissions, and propose alternatives to lessen air pollution.

Neighbors for Clean Air sent its good neighbor agreement to Daimler CEO Martin Daum in the fall. Schroeder said they never heard back. After that, neighbors started a postcard campaign.

"He [Daum] got probably between 400 and 500 postcards, and we have never heard from him," Schroeder said.

Erdy said said the emissions from the Western Star facility "are well below permitted levels" as set by DEQ and EPA. He said Daimler has decided not to agree to contracts "with non-governmental organizations such as Neighbors for Clean Air."

"Contractual arrangements with either individuals or environmental activist groups are not necessary to achieve substantive environmental improvements," he said. "They are prohibitive and do not achieve the goals of the common cause."

Air quality on campus

Although neighbors have voiced their complaints, they aren't the only ones in North Portland worried about air quality. UP students, faculty and staff also show growing concern over industrial air pollution in North Portland. Daimler is just one of several companies on Swan Island whose facility emissions are toxic.

Jeff Rook, UP's environmental health and safety officer, said he's had complaints about several smells on campus. He said concerns about a gas - like smell are most common. Rook said the sulfur smell is probably due to Swan Island companies like Vigor Marine that make and finish boats, not a leaky gas pipe.

Rook agrees that the effect of the paint smell from Daimler is subjective. Some people aren't affected by smell and others are more sensitive and have a stronger reaction.

"It's kind of a needle in a haystack trying to figure out specifically what people are reacting to," he said.

Santana is concerned about Daimler's effect on the air quality but knows it's not the only facility emitting toxic chemicals into the air.

"The thing that's really scary is in this area we're at ground zero for emissions," he said. "What we are dealing with here in the University of Portland community is a very toxic air shed."

Santana hopes the University sees the benefit in addressing air quality, and thinks the University can do a better job of raising awareness by encouraging students to register air complaints, investing in monitoring equipment and supporting those groups who want cleaner air.

"If we're trying to be a model of sustainability, then we have to put our money where our mouth is," he said. "It's really an issue of health and safety for the students."

Students study air quality

Some students are also taking action to define and register on-campus odors.

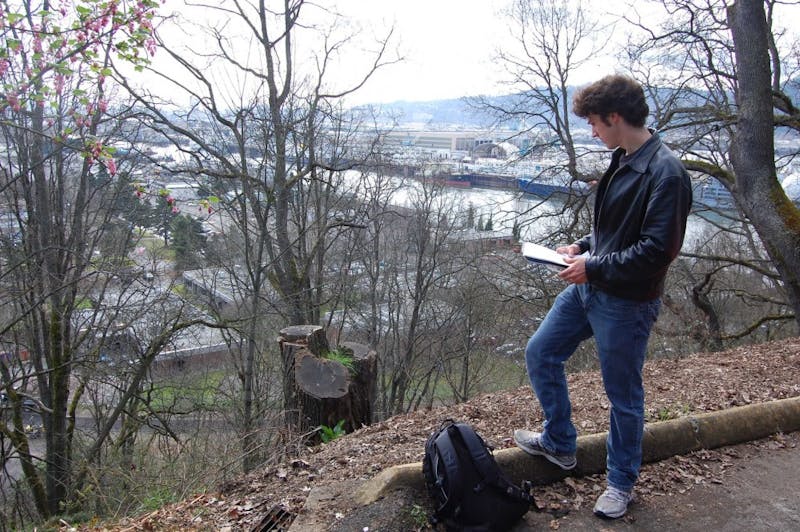

Through a weekly environmental science class, titled "Air Pollution," 13 students check the air from 10 locations on campus and record what they smell and how often they notice an odor.

Senior Matthew Abely, an environmental ethics and policy major, said the class focuses on key intersections on campus. They test the air four times a day, once between 6 and 8 a.m., 10 and noon, 3 and 5 p.m. and 6 to 8 p.m.

"We have to go around and basically take a whiff of the air," Abely said.

Jim Houck, an adjunct professor teaching the class, said the students classify the smells as either "chemical -like" or "organic - like." Houck said the testing can be tricky because people interpret smells differently.

"It is subjective, but if you do it enough times the truth comes out," he said.

Houck said the class's findings are not definitive or conclusive, but they do help to contribute facts to the conversation about air quality.

"You get a lot of this rancor going on and this exaggeration, but very few facts," he said. "What I'm trying to do with this class is get unbiased facts."

Rook said the work done by the class allows the University to better understand what is in the air and provides the "possibility for air monitoring on targeted days to capture odors."

Area six, near the edge of campus and the bluff and above the Daimler plant, not only smells the most like paint, but has the highest frequency of smells. According to the Abely group's research, 36 percent of the time, students noticed a "chemical - like" odor and eight percent of the time noticed an "organic - like" odor, meaning there was a noticeable smell 44 percent of the time. Station six has a smell 18 percent more often then the next most odorous location, according to the research data.

Abely said the smell could be stronger, but any pollution should be a concern. He said without a conscious effort to improve air quality, it will become an even bigger problem.

"Something needs to be done about it," he said. "It's not going to be Beijing or London fog. It's going to be a slow build to a big problem."