In 2017, The Atlantic journalist Noah Berlatsky wrote an article about the rise of the alt-right after the Trump presidency titled, “The Case Against Free Speech for Fascists”. This article contained a quote that resonated with me about why views in support of discrimination and prejudice hold a different weight than a mere impolite expression of free speech.

He says, “Hateful, bigoted speech, if left unchecked, leaves marginalized people feeling vulnerable and endangered — for good reason. If you let people spew bile, the folks at whom they spew bile will leave. You’ll be left with a safe space for hateful speech in which the only speech on offer is hate.”

The editorial “Why we published ‘We have come too far’” was published to explain the choice to share the contentious article by Br. Benedict. The editorial expressed that being an ally of the LGBTQ community and being supportive of the free speech rights of those who support LGBTQ exclusion are not antithetical beliefs to hold. The article goes on to say, “In fact, the open exchange of diverse perspectives is what ultimately cultivates a safe space for marginalized communities.”

I resent the co-option of social justice language here to imply that one has the obligation to platform prejudice like Br. Benedict’s piece, and that doing so could be beneficial to the people who are targeted by prejudice. I raise the question: Where exactly is the safe space that gets cultivated through the inclusion of rhetoric that denounces those very marginalized communities? In turn, if people who espouse intolerant beliefs are allowed to occupy such significant real estate, what does that suggest about the nature of the safe space?

I agree that one can feel genuinely passionate about social justice causes and also espouse free speech centrism as the editorial suggested. However, I also believe that the trade off that occurs when the interests of these two belief systems conflict is something that is neither radical, nor responsible.

The editorial cites a quote from a 2019 Beacon article on media literacy, that reads: “Many people, especially in the era of the curated social media feed, expect to only read, watch, and listen to information that supports their worldview. They do not even want to hear of the other side. But for a news organization to not present all sides of an event or situation, or to fail to report that a public event happened, would be misleading and not in line with journalism’s mission.”

With regard to the quote’s first half, I think that using this tone in particular to justify the publication of “We have come too far” is an unfair judgment of those who felt strongly about the article’s content. A negative critical response from the audience does not equate to an inability to hear the other side out, so to speak.

In this circumstance, the context also differs from not wanting to witness a harmless hot take. Having your identity respected at the institution one works and studies at is a matter of social justice and human rights. It’s so important that activists have been fighting for it for years, and it’s since been baked into our legislation.

The benefits of such inclusion are greatly restorative and affirmative to marginalized communities. People in opposition to this come from a place of intolerance. The extension of their beliefs comes at the expense of furthering inequality. Morally, these viewpoints are not equal. Is the wrong side of history truly a “side” worth engaging?

I agree with the second half of this quote and how it describes the mission of journalism. Of course it is crucial that the news presents a well-rounded recollection of the world around us in order to better all of our understanding. Yet in the context of “We have come too far”, can we honestly say that goal is being achieved? The opinion piece that “We have come too far” responds to, titled “We have come far, yet not far enough”, is a meticulous and profound record of the way structural inequality at UP has shortchanged LGBTQ students.

It documents the reality of these issues from a variety of perspectives, both from affected students and from experts on the subject of LGBTQ livelihood. There is even representation of the opposition in this article, through quotes from Fr. Paul Scalia and University leadership. This piece is an exemplary representation of the definition of journalism from the 2019 Beacon article. Entirely within “We have come far, yet not far enough”, the aforementioned standards of “report that a public event happened” and “present all sides of an event or situation” have been fulfilled.

Meanwhile, “We have come too far” provided almost no additional context, information, or insight to the issues outlined in the original article. It responded only briefly to the concern that the chapel here will not marry same sex couples. The remainder of the article was used to argue for the alienation of LGBTQ people from identifying with Catholicism, using typical tropes of homophobic biblical interpretation.

It is an extremely pervasive understanding in culture at large that the Catholic Church is not particularly welcoming to LGBTQ people. Through the Catholic Church’s history, this dynamic becomes apparent; regardless of if you are LGBTQ, and regardless of if you grew up in the church there is suggestion of this. Intolerance and the Church are so often conflated that there are several courses at the University of Portland with curriculum specifically dedicated to dispelling this assumption.

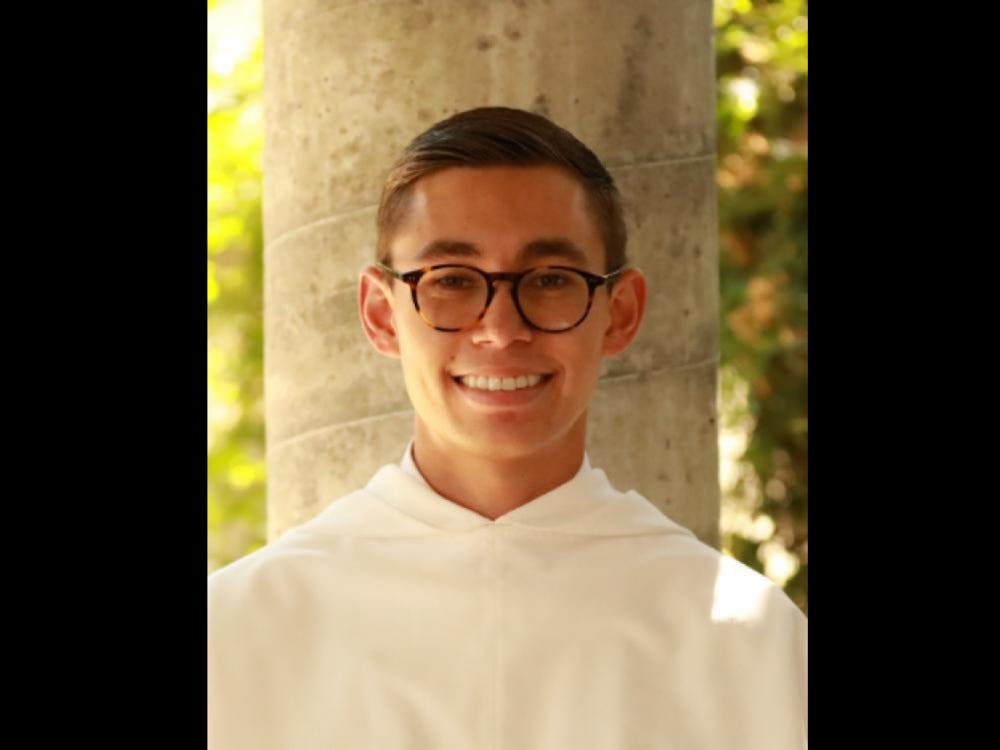

Those who have faced homophobic and/or transphobic hostility would have found the rhetoric of Br. Benedict to be very familiar indeed. On the other hand, there is the revelation that Br. Benedict graduated four years ago. I’m sure it’s also safe to assume he has not been at the other end of discriminatory policy and microagressions toward LGBTQ students as described in the original article.

He doesn’t have an intimate understanding of current student life or of the specific challenges of being an LGBTQ student at an institution that offers inconsistent support at best. If depth of discussion is what is being sought, then Br. Benedict’s narrow-minded perspective is not adequate or relevant to achieve this.“We have come too far” teaches nothing new or valuable by reiterating this harmful ideology on a large platform.

I would denounce free speech centrism that comes at the expense of marginalized communities with a quote from that very 2019 Beacon article that states: “It’s important that a commitment to presenting all sides does not mean a Donald Trump-esque ‘both sides’ false equivalence. Many journalists are also aware that what and who they even decide to cover matters, and can provide a platform for nefarious forces if not done correctly.” Both-sides-ism may be a tempting medium from the polarization and the uncomfortable accusations of favoritism that plague modern political discussion.

In reality, all that is accomplished by treating “both sides” of social justice issues as equal is the reinforcement of existing structural inequality. Those who already have privilege in a heteronormative, patriarchal, eurocentric society get yet another space to be oppressive. Marginalized communities have to fight that much harder in response.

It’s not necessary to platform intolerance freely so that the audience may “learn to navigate controversial opinions” or to prepare to enter “the adult world”, as the editorial posits. Those of us who live as gender, sexual or racial and ethnic minorities reckon with prejudice and its implications constantly. We already know how to navigate bigotry, for it is essential to our survival. To even be in the position to view these matters as a novel debate is a demonstration of a privilege that marginalized people do not experience.

Bias is inherent to our psychology. A publication does not have to attempt to eradicate every trace of bias in order to be reliable or trustworthy. This is another aspect of fair political discussion that I think both-sides-ism gets wrong. Some of the most respected news organizations in the world would be described as having a slight left-leaning bias, for example.

If it’s authored by humans, who bring to the table a rich culture of experience and knowledge that is unique to their own lives, then it is not unbiased. And that’s okay. Being conscious of where this bias might lead us is the important part.

With such a large platform to spread ideas (that arguably reflect the University as a whole, for better or for worse) critically considering the inclusion of potentially harmful works is not censorship. I’d say it’s an act of discerning curation.

Jordan Ducree is a junior at UP. She can be reached at ducreej23@up.edu.

Have something to say about this? We’re dedicated to publishing a wide variety of viewpoints, and we’d like to hear from you. Voice your opinion in The Beacon.