Over Fall Break, University of Portland’s non-faculty employees were given one paid day off, a “Pilots’ Staff Appreciation Day.” At the end of September, the University also paid a $1000 “Pilots’ Staff Appreciation Bonus” to staff who make less than $75,000 a year.

In the email announcing the bonus, Vice President for Financial Affairs Eric Barger was direct:

“Like so many other businesses and organizations across the nation and here in Portland, UP is currently understaffed,” he wrote. “Indeed more than 10% of our budgeted staff positions are open.”

The bonus and the paid day off were an acknowledgement that current staff are often doing double or triple duty or more to make up for the vacancies.

Left unsaid in the announcements: Perhaps the “Pilots Appreciation” measures would also be an incentive for those remaining employees to stay at UP, and not join the “Great Resignation.”

Beyond the veil of this Great Resignation is the face of a larger issue, which has been present even before COVID-19. According to staff, some employees are just not happy working here.

In fact, over the past year, some have been meeting to try to organize a Staff Senate — modelled after the faculty’s Academic Senate — to unify their voices and express their concerns about working conditions, salaries and other issues.

Others, however, have decided it’s time to move on.

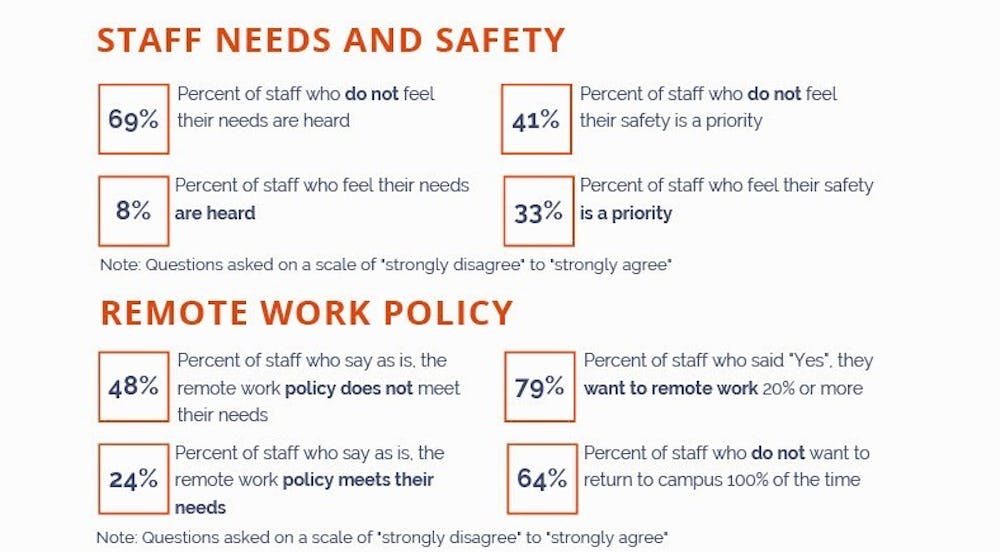

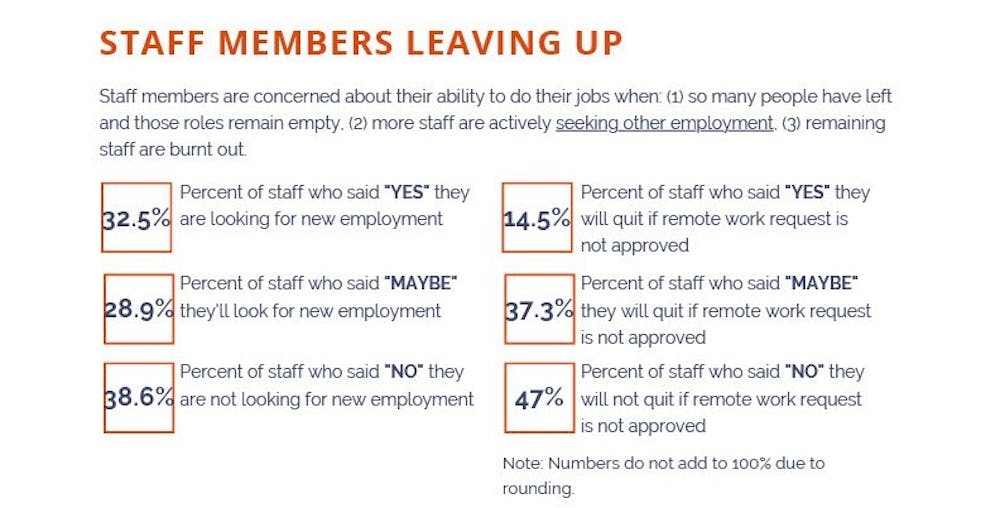

In a survey by the Staff Senate Working Group in July, 32.5% of staff said they were looking for new jobs.

Screenshot of July 2021 staff survey.

The Beacon spoke to several staff employees who have left UP over the last 18 months to discuss the problems they faced working here, and their reasons for leaving.

The return to campus and the Remote Work Policy

At the beginning of the pandemic, many people would have given anything to be back in-person and on campus again.

But that was a long time ago, and things have changed.

Although vaccinations became widely available, the post-vaccination relief was short-lived when the extremely volatile Delta variant emerged in June, and now we might face a new threat in Delta plus.

“The pandemic shifted things in a very dramatic way,” former Assistant Director for Student Engagement Lyndsy Manz said.

Manz, who had 15 years of experience in higher ed at Virginia Tech, the University of Arkansas and Baylor University, was named “Staff Member of the Year” by UP’s student government (ASUP) at the end of her first year here.

When she moved her family from Indiana to take the job at UP in January of 2020, she hoped to take advantage of one of UP’s signature fringe benefits — the Home Buying Assistance program — that financially helps employees purchase a home in the North Portland neighborhood.

In March of 2020, the University pulled that program in response to the financial pressure from COVID-19. Her salary at UP was $49,200, Manz told The Beacon.

With the home subsidy benefit gone — and not returning until August of 2021 — Manz, a mother of three, had to move her family much farther away from campus to a more affordable neighborhood in Gresham.

The unaffordable cost of living on her salary pushed her out of Portland. The family also had to purchase a second car since she would not be able to walk or bike to UP’s campus, as she had hoped.

“That was a big shift from my hope and expectation of being in and near campus life, and a part of the community, to ‘Oh, I can’t afford to do that if that benefit is not here.’” Manz said. “Now I’m a 45 minute drive away from campus.”

Manz also pointed out that an increasing amount of her time was being spent on the computer, not with students. She was processing reimbursement requests, PCard purchasing on behalf of clubs and documenting financial transactions in Engage.

“My time invested in this does not involve physically being with others, rather a dedicated time for computer use,” she wrote in her Remote Work Request to Vice President for Student Affairs Fr. John Donato.

Manz asked for a rotating schedule in her work from home request, working remotely 2 days one week and 3 days the next. She did, however, offer flexibility to UP.

“This of course would be subject to adapting to the needs of the Office of Student Activities as well as any other regularly scheduled committee or campus meeting I might join,” Manz said in her request.

In June, when the administration announced a mandatory return to work at the beginning of August, staff members, like Manz, had to scramble to accommodate.

Many staff became nervous about returning to campus. Some employees concluded that working remotely to that point did not compromise the quality of their work and that the more flexible workstyle improved the quality of their lives.

UP employees are not alone. Many surveys have shown employees across the nation value more flexible work arrangements, and are leaving their jobs that are not allowing remote work or flexibility. Companies are accommodating them to retain talent.

The staff survey showed that 48% of staff did not feel like the remote work policy met their needs, and 79% said they wanted more than 20% remote work.

Screenshot of July 2021 staff survey.

Final decisions on remote work requests are made by the vice presidents of each division. The Remote Work Policy allows for 20% remote work — or one day a week — but many requests have been denied altogether. It can be increased slightly “if it makes operational sense”, according to Acting President and Provost Herbert Medina. Remote work on Mondays and Fridays is discouraged, according to an email to staff.

“While the policy is open to 20% remote work (i.e., one day weekly), it really depends on the position’s scope of work and whether it lends itself to this application,” Donato said in an email. “It is not automatically assumed that every job can be effectively done by working remotely.”

For some, this decision felt like an ultimatum. Nearly 15% of those surveyed said they would quit if their remote work request wasn’t approved.

“The final straw for me was the [return] to campus, and the way it was decided without feedback or input,” Manz said. “It felt dismissive of the year and a half we had been working remotely and getting a lot done.”

Screenshot of July 2021 staff survey.

With the extended commute, Manz said she would barely have time to see her kids given the late night schedules of student leaders on campus.

“I put my remote work request in and communicated why I asked for that, how I felt like that served not only me and my family’s needs, still in the pandemic, but also how I felt like I was better able to support student leaders working on an evening schedule,” Manz said.

“My remote work request was denied and there was no room for negotiation,” she continued. “I understand, we have a shared value, but a difference in perspective of how we can achieve community building. Without that flexibility, I just didn’t see a healthy sustainable way forward when my kids [weren’t] even in school yet.”

Manz left in August, and is now a Surrogate Coordinator at Northwest Surrogacy Center, which allows remote work.

Former Administrative Assistant for the Office of Student Activities Elizabeth Aguilera applied for remote work until November. Her husband has been going through chemotherapy, and Aguilera didn’t feel safe returning to her office in St. Mary’s.

“I felt like the time Summer 2021 rolled around, the University wasn’t doing enough to prioritize the health and wellness of staff,” Aguilera said. “An example of that was that my workspace in St. Mary’s had no ventilation, and there wasn’t a plan to remedy that before I went back into that space.”

Her Remote Work Request was denied, along with all other staff employees who applied to work from home in Student Affairs.

Aguilera was eventually granted remote work through human resources because of her unique situation. But by the time she had heard back, Aguilera already decided to resign.

Aside from her safety concerns, Aguilera said that the administration did not consider all the changes that had been made in employees’ lives since the pandemic began.

“There wasn’t a recognition of the logistical difficulty that this might bring for some people who may have sold a car while working remotely, or moved to a different area, or had to arrange for childcare for their children,” Aguilera said.

“They could’ve done better by providing services for people who might find returning to work traumatic,” she added. “I personally lost a family member to COVID before vaccinations were available, and not considering that there are people who have different levels of comfort given their own personal experiences with COVID was kind of an oversight.”

Former Associate Director of Annual Giving Olivia Bormann, who resigned in September, said that UP would benefit from a more flexible policy, and that other institutions are offering more flexibility.

“Why don’t we have a work from home policy that’s flexible and can meet the needs of everyone?” Bormann said. “We’ve been here doing things remotely for the past 18 months, and now all the sudden we can’t do it any more? It’s still a pandemic.”

The University has no plans to adjust the remote work policy. Administration decided to bring staff back in-person to accommodate for students, and because the UP community thrives when it’s in-person, Medina said.

“If our students are going to be on campus, then we need most of our staff to be on campus as well, most of the time,” Medina said. “I understand that that might be different than what other employers might be doing, but again, we’re an on-campus community.”

Staff members point out that at least some of their work does not involve being present with students and faculty are being given more flexibility with remote work. This is partially because they do not have set hours outside of their teaching schedule, office hours and other commitments, according to Medina.

However, staff point to a double standard at UP, given the fact that faculty were offered the option to teach remotely this semester, while many staff were required to be in-person five days a week starting Aug. 2.

Medina highlighted the work of those who have been showing up on campus throughout the pandemic, and the equity issues that may arise for those who can’t work remotely.

“They’re real heroes,” Medina said. “For example, the folks who show up for the night shift, the folks in Physical Plant. If you’re a groundskeeper, you can’t say ‘I’m going to work from home, I’m going to telecommute.’ Our Campus Safety officers can’t say they’re going to do remote patrols.”

Faculty members will be given the option to teach remotely next semester due to medical considerations. Otherwise, they will be expected to teach in-person, Medina said. Approximately 95% of classes will be in-person next semester.

Communication, belonging and a voice on campus

When she resigned, Aguilera didn’t have another job lined up.

“I was frustrated with some of the inactions of the University, and some of the difficulties I was facing,” she said. “I felt like I endured a lot during the prior year, like everyone had, and that included working really hard during furloughs.”

In August of 2020, many staff members were furloughed due to the financial damage dealt by COVID-19. Some staff remained partially or even fully furloughed throughout the last academic year.

“Once those [furloughs] were lifted, it didn’t feel like there was very much appreciation for staff,” Aguilera said. “And in the prior year in particular, it felt like staff voices weren’t valued and considered.”

Shortly after leaving, Aguilera found a job as communications and project coordinator for Social Venture Partners Portland.

Of the 105 respondents in the staff survey, nearly 70% said they do not feel their needs are heard. Bormann, who helped prepare the survey, said part of the issue is communication.

“Admin doesn’t communicate with staff proactively, so information is handed down,” Bormann said. “There isn’t a structure for staff to communicate in a really systematic way, so you’re always in the dark.”

Courtney Campbell, former assistant director of first year experience, said there was a long wait when getting responses from administration.

Courtney Campbell, the former assistant director of first year experience, left UP in September 2020.

“It was a lot of waiting, a lot of worrying, and sharing our opinions to our bosses and our managers and thinking ‘Well hopefully they listen,’” Campbell said. “I didn’t feel like my voice was being heard.”

Transparent communication with administration has been a topic of concern for staff members, especially given the unpredictable conditions of the pandemic.

Manz, who has had experience with other higher-ed institutions, says that UP is unique in terms of how they pass along information.

“There is not an up-and-down the org chart communication feedback loop,” Manz said. “There just doesn’t seem to be a pathway for staff to offer feedback. For me as an employee, it was a disengaging experience to not feel welcomed to contribute to the excellence of the University.”

Aguilera, Bormann and Manz, along with other anonymous respondents in the survey, said the way the administration communicated the return to work didn’t allow for feedback from staff. This has been a common theme in policy decisions, according to Aguilera.

“We would learn about policy changes from emails that everyone was getting at the same time, including students,” Aguilera said. “It was frustrating to not even have an idea of what was coming.”

A huge factor impacting access to information at UP is the fact that it is a private institution, and is within its rights to withhold information, according to the former Director of Institutional Research Elizabeth Lee.

She knows, however, that this lack of transparency is challenging.

“I wasn’t surprised that folks were feeling like, ‘Well why isn’t the administration telling us what’s happening with the pandemic?’ or ‘Why aren’t they telling us what they’re going to do to address historic marginalization of faculty and staff?’” Lee said. “It was just part of the embedded culture. It’s not endemic to any specific person, it’s part of the administrative culture and it takes time to uproot that.”

The lack of transparency and difficulty communicating with administration have made staff feel alienated — something that can heavily affect whether someone chooses to stick with their job, or not.

Staff compensation

Oregon ranked fourth in CNBC’s top 10 most expensive states to live in for 2021. With the price of living in Oregon climbing, some staff feel they aren’t getting appropriate salaries and wages to keep up.

“The entry level salary range that UP provides is not livable,” Campbell said. “I think UP does a really great job at hiring people who work really hard and love what they do. In that same vein, I think they know, because they hired that kind of person, they can play the, ‘You do it because you love it.’ Sure, but also we do have bills to pay.”

The Staff Senate Working Group’s survey collected information on how much staff members are being paid. Over 50 staff members responded, and 42 of them reported having salaries below $50,000 before taxes.

“I think our staff are underappreciated and underpaid,” former Associate Vice President for Student Affairs Matthew Rygg said in June. “It’s [the] staff and administration that have to carry out these plans and help the University pivot in these difficult times, and we’re doing that without paying people appropriate salaries.”

On average, those who responded are making an estimated $22.67 an hour, or $47,162.76 annually before taxes. This data may not be completely reflective of entry level salaries at UP.

“My salary was barely above the living wage for a person in my position — two adults working, one child,” Aguilera said in an email.

The University does not list estimated salaries or wages on their job postings or website. Portland State University’s average staff salary is $66,580.

“Most entry level coordinators/program assistants/advisors/assistant directors (folks that were at my peer level or who I was supervising) were making a salary of $36k-$50k,” Manz said in an email.

Medina recognizes that salaries at UP may not be competitive compared to similar universities, and says there is a plan in the works to adjust them.

“We do want to do a comprehensive look at staff salaries,” Medina said. “That’s something that I’m hopeful the new Vice President for Human Resources will be able to undertake. That’s a project I think needs to take place. We’ve done something similar for the faculty through a faculty compensation committee.”

Intent vs. impact: diversity, equity and inclusion

Before leaving in the spring, Lee was working with other staff members, like Bormann, to move change forward at UP and support people of color in the community.

“In early 2020, once I saw that the Black Lives Matter movement was really forcing the issue and forcing the conversation, I thought, ‘This is the perfect time to bring forth these issues and not let it be a one time conversation,’” Lee said.

There are many staff and UP community members who are committed to DEI work at UP, putting in time and effort outside of their job descriptions, Lee said.

“That was a really amazing summer in a number of ways,” Lee said. “The [work] felt very effortless and meaningful, but we weren’t appreciated. That was the part with that work that was missing.”

Lee came to UP in part because of the influence Former Vice President for Human Resources Sandy Chung had on her when they met. Reading what Chung wrote in her Beacon Op-Ed pushed Lee away from the University.

“That was a real tipping point for me,” Lee said. “I see [Sandy] as such an amazing leader at UP. She was one of the reasons I took the job at the time. Seeing what she was struggling with at her level within the organization was really something that tipped the scales for me.”

Bormann described DEI work at UP as emotionally draining, and often hopeless. She attributes this struggle as one of her biggest reasons for leaving.

“I have run myself into the ground trying to make this institution a better place, because the Black, and brown, and queer students who go here deserve to go to a place that loves them and affirms them,” Bormann said. “I did everything I could while I was there, and I’ve just had enough.”

“I started off assuming good intentions, and that if we did the work things would change,” she added. “It just became really clear that nothing was ever going to change, or at least that’s how it felt to me.”

Staff members have described administration as patriarchal, and slow to make the necessary changes to foster an inclusive work and learning environment. Part of this has been attributed to the hierarchical structure that dominates University operations.

“The Catholic Church is a very hierarchical institution, and universities are also hierarchical,” Rygg said in June. “So when you have a Catholic university, it’s by default very hierarchical. Hierarchy doesn’t work so well when we’re trying to dismantle power and privilege and make more equitable systems.”

Aguilera points out that many people of color occupy lower level staff positions, and that when the University is not accommodating staff, it is right in line with not accommodating people of color.

“I think it’s important to point out that the University said they wanted to do more things towards equity and diversity, and a lot of the people who have been leaving are people like Olivia... and myself,” she said. “I’m a Latina, and I did not get paid very much at UP.”

Staff members have been dissatisfied with the University's response to DEI issues, including the results from the investigation which confirmed that the administration failed to foster diversity and inclusion.

“It really comes down to that concept of intent vs. impact,” Lee said. “A lot of the responses from the administration, including the response from the investigation, is a lot of ‘Well we intend to do all these great sounding things.’”

Despite the struggles she and others faced trying to progress diversity and inclusion, Lee is still hopeful that the University can continue to change.

“We knew that the institution could be better because there was, and I’m sure there still is, this critical mass of folks very onboard with active engagement with DEI,” Lee said.

The University is taking action to improve DEI, according to Medina. The Presidential Leadership Cabinet (PLC) and the Provost’s Council went through a DEI training in August, and a DEI consultant has been retained and will be on campus in November, Medina said.

“I’ve been working on DEI issues since the time I was a graduate student,” Medina said. “This is at the heart of what I like to do and what is important to me in higher-ed. I’m going to continue as best as I can to push the institution, to challenge the institution, to challenge us to move forward on DEIJ issues.”

A call for a staff senate

Members of UP’s faculty meet once a month with administrators to discuss University operations, policies and issues they may be facing, among other things. This Academic Senate serves as a line of direct communication between faculty and the administration, something that staff members are longing for.

“I was part of the initial team for planning and identifying how this can happen,” Campbell said. “I think it’s critical for the University to have a Staff Senate. We know the Faculty Senate have fought hard and difficult battles for things like pay equity, and been successful. To be able to have a voice and a seat at the table, it’s critical for any kind of institution to have their people be represented and their voices be heard.”

The group would meet regularly to create community, provide information and suggestions to University administration, serve as a liaison between staff, Academic Senate, the Associated Students of University of Portland (ASUP) and the administration, and appoint representation to all University ad hoc and presidential advisory committees, according to the Staff Senate proposal.

After close to a year of work, Aguilera and Digital Lab Coordinator José Velazco presented the idea to the PLC in July. Both ASUP and the Academic Senate have expressed support for a Staff Senate.

Medina also expressed his and the PLC’s support for this group at convocation.

“One thing I’m hopeful about is there’s a grassroots movement to start a Staff Senate,” Medina said. “I think that will be a mechanism to allow us to gather organized feedback.”

For those staff members who have felt disconnected from UP, this Staff Senate may serve as a way to help bridge the gap and tackle some of the issues they have been facing.

“I never felt a part of the UP community, I never felt like I mattered, I never felt like I belonged,” Bormann said. “I think having an organized body is a start to that.”

Keeping talent, and finding it

UP has been scrambling to fill in vacancies throughout the semester, and the task becomes even more difficult as staff continue to leave.

The University faces competition from other companies and organizations that are offering the flexibility and work culture staff say UP denied them.

In the meantime, dozens of staff jobs sit unfilled at UP — there are currently 38 staff positions posted on the job board. UP is offering a $1,000 hiring bonus for some of those jobs, but the candidate pool is slim in many cases.

Austin De Dios is the Editor-in-Chief of The Beacon. He can be reached at dedios22@up.edu.