During Black History month we remember inspiring leaders like Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, Ida B. Wells, Malcolm X, Huey Newton and Martin Luther King Jr. We read about protests, marches and sit-ins. We look at old photographs, watch documentaries and listen to speeches.

During his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, Martin Luther King Jr. said that he hoped that his children would one day be judged, “not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” And while very few people would argue with this sentiment, over time this message has become distorted. Not judging someone based on their race or ethnicity became equated to ignoring their racial or ethnic identity all together. This is called “colorblindness,” which, while usually well-intended, actually belittles and devalues the identities and experiences of people of color.

So while Black History month and Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech may have been directed toward the specific experiences of black Americans, this resulting colorblindness and other modern forms of racism affect all people of color — whether they’re African-American, Chicano, Filipino-American, Lakota, Caribbean, Saudi, Latina or any other race or ethnicity.

We do not live in a post-racial society.

Yes, people of color have made major strides toward political, economic and social equality. And this month in particular we celebrate the accomplishments of Black Americans throughout history.

But sometimes when people talk about race and racism — within the context of black History Month — they talk about it as if it only existed within a historical context, as if DuBois or King “cured” the United States of its racism. Depicting racism as a problem of the past is both narrow-minded and short-sighted.

While it’d be really nice to say the U.S. has been “cured” of its racism: It hasn’t, and it can’t be. And here’s why:

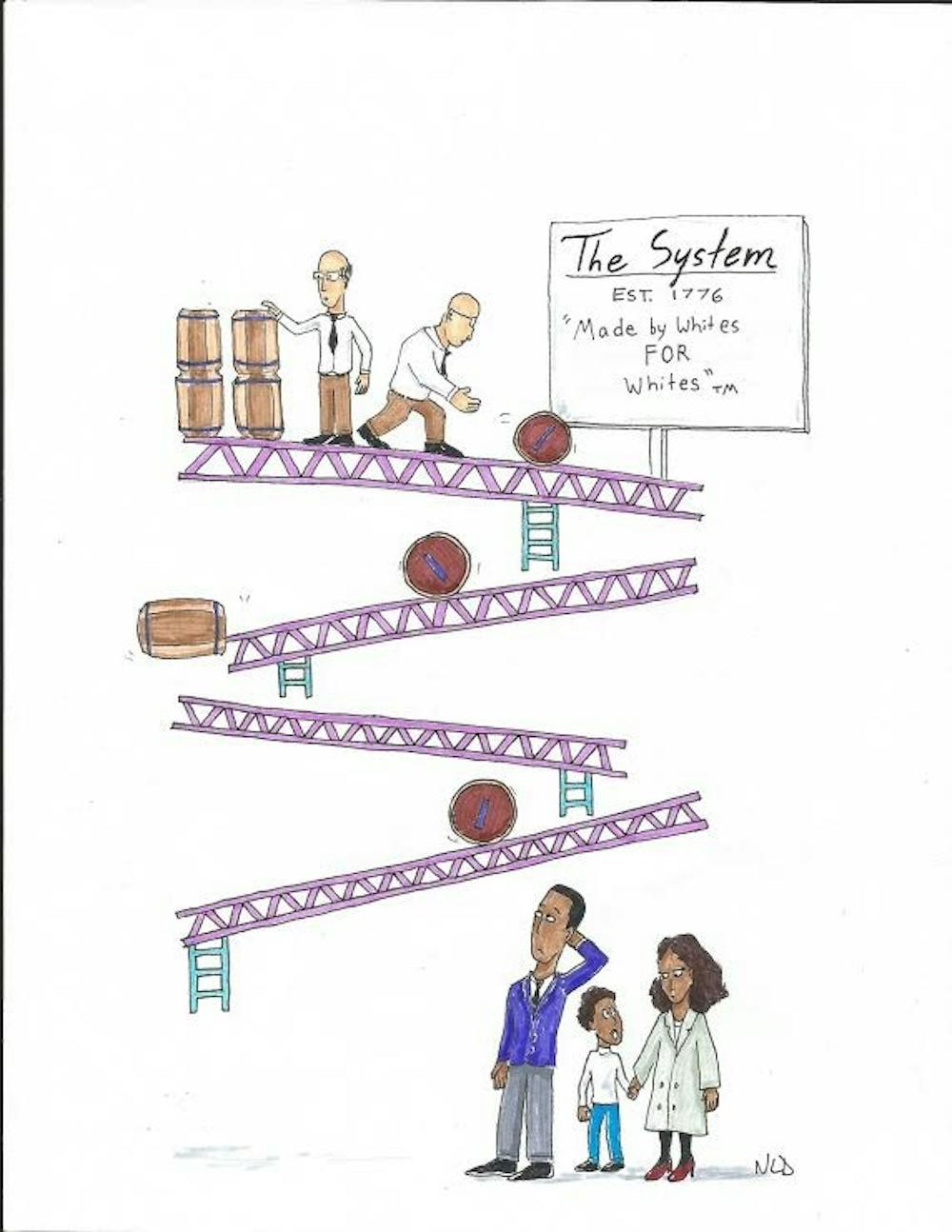

The United States’ independence and success as a nation was built on racism.

While it’s an uncomfortable truth, the United States is structurally and systemically racist.

Slavery, an inherently racist institution in this country, allowed white settlers in America to accumulate wealth, which eventually was used to fund the American Revolution. Literally, the United States as a nation could not exist without the racial oppression and exploitation of African slaves. But more than that, this racist ideology was then written into rules and codes that created the roots of our economic, political and social realities.

True, overt forms of racism have greatly diminished over time, and individual forms of racism have become less and less socially acceptable. But, like a complex bacteria adapting to its environment, racism has evolved. Racism today, in most cases, is much more subtle, more covert — and that makes it even more insidious.

For example, “legacy admissions” into college privileges students whose parents or grandparents attended the same institution. On face value, this doesn’t seem inherently racist, but consider this: Many colleges were, at some point, segregated, and for many decades black Americans weren’t allowed to attend college or couldn’t afford it. That means more white alumni have the opportunity to take advantage of legacy admission than alumni of color.

Critiquing legacy admissions might upset some members of the UP community. Doubtless, there are legacy admissions attending school here right now. The point of this critique is not to point fingers at individuals. Sometimes individuals perpetuate racist ideologies, but more often, structures perpetuate racist ideologies and individuals just operate within these structures.

We need to change the structures we operate within.

But structural change is difficult. It requires a lot of time and energy, and there’s always some backlash. People that benefit from unjust systems rarely want to change them, whether they realize the systems are unjust or not. And like the saying goes, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” If someone doesn’t recognize that a system is “broke,” they’ll have no justification or motivation to fix it. And that’s where we can begin: Learning about the system and being willing to see where the system is broken.

Bringing more diversity to our campus, through more intentional hiring and admissions practices, is an admirable goal to have. But even more importantly: We need to appreciate the diversity we already have on our campus. In order to protect and appreciate the varying racial and ethnic experiences of our diverse student body, we need to be more educated and more aware. Because ultimately, education and awareness are the first steps toward structural change.

On our campus that means more programming around the effects race and ethnicity have on our community. It means more cultural events, lectures on race issues and campus-wide discussions on the way “isms” affect our community. In our dorms that means holding discussions about the impact race has in every wing, and holding residents to a standard of respect and acceptance of diversity.

In our classrooms that means more diverse readings and topics discussed in EVERY class – and requiring every student to take a cultural competence class. Social work, sociology, English and history should not be the only places we discuss diversity and cultural understanding. We challenge every professor to critically assess the messages they’re intentionally or unintentionally sending to their students through the readings, lectures, assignments and activities they plan.

We, as a community, should always strive to combat the systemic and structural forms of racism we encounter every day. But some of us may not have the power to affect structural change, so all we can do is start the conversation. Because, if we’ve learned anything from recent history it is: Not talking about race doesn’t make inequality disappear. Sometimes it even makes it worse.

Talking about race doesn’t mean knowing every politically correct term. It doesn’t mean knowing every current event or statistic. And it doesn’t mean knowing every historical event or famous figure. If we’re genuine and open to honest communication, we can have meaningful discussions and learn something about ourselves or the people around us.

This month, while dedicated to the black Americans that fought against slavery, lynching, segregation and discrimination, is also an opportunity for everyone to discuss issues around any race or ethnicity. You could discuss issues around race in a classroom discussion, talk to your professor about a lack of diversity in their required reading, confront someone when they say a micro-aggression, or critically assess your own unconscious biases.

We all have a role to play in making our community more inclusive for anyone. Changing our community won’t be easy, but we have an obligation to try. Having a conversation is a good start.