Last fall, Public Research Fellows and the social justice minor at UP were working on a Clark Library exhibit that would showcase archival research done by students in collaboration with Don’t Shoot PDX, a nonprofit organization promoting social justice and civic engagement.

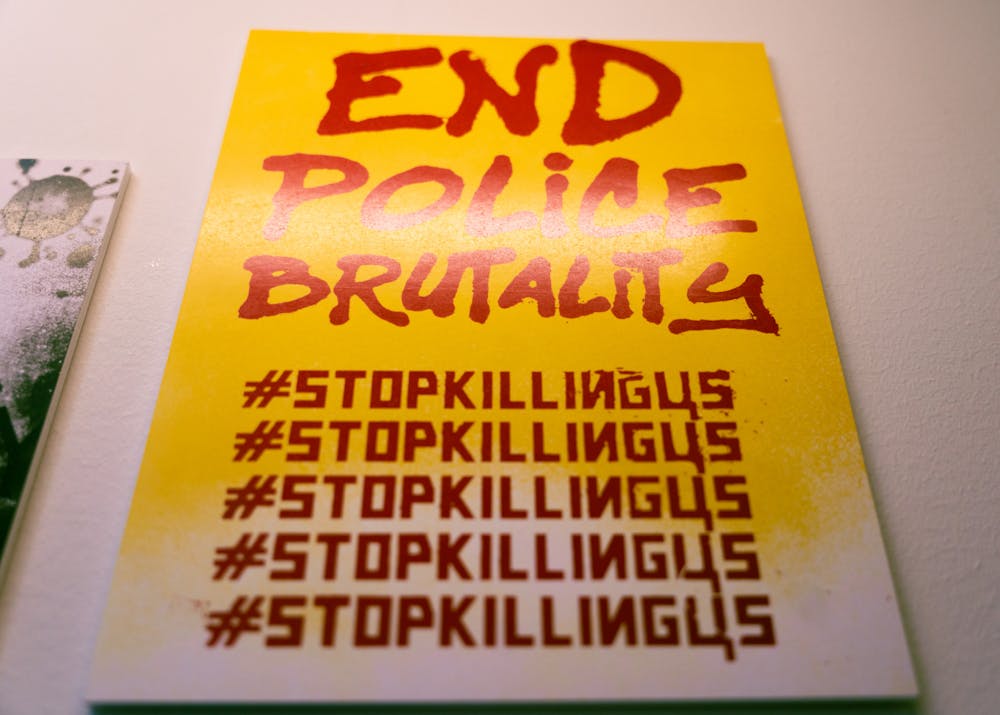

Now, anyone can engage with their work at the library’s Covert Gallery, where they’ll find zines brimming with commentary, letters, photographs and even clippings of Beacon articles dating back to the early 1960s — all highlighting the history of racial injustice and collective resistance in Portland and at UP.

Social justice minors Murphy Bradshaw and Kerri Osumi, advised by sociology and social work instructor Lizz Schallert, spearheaded the project in Nov. 2023. For Schallert, the exhibit has been made possible by library staff as well as Taishona Carpenter and Teressa Raiford, who founded Don’t Shoot PDX after Raiford’s nephew was fatally shot in Portland in 2010.

“They [library staff] have been just so unbelievably helpful in finding ways to like thematically present that material and work,” Schallert said. “It's just a lot of content. We have hundreds, literally hundreds, of archives, and Tai and Teressa also have tons of community archives of their incredible racial justice work in the community.”

Effectively presenting that much information has been no small task. Looking for ways people can engage with the material, the group emphasized making it tangible for others — one of Carpenter and Raiford’s major influences on them.

“They [Carpenter and Raiford] were always very excited about people literally touching the archives,” Schallert said.

Although they were unsure at first about the time and work needed to make that happen, Schallert quickly saw that it was integral to how people would learn from research.

“It was so obvious that that was so important because people actually like touch them and read them and it wasn't just a theoretical exploration of what archives are,” Schallert said.

The hard-copy zines found inside Clark are a story-like exploration of how racism and its resistance permeated life in Portland from archived Beacon opinion articles to photos of UP’s Black Student Union dating from the 1970s.

More than just a collage, senior social justice minor Murphy Bradshaw thinks archival research can become its own form of storytelling.

“I think that archival work is always a story being told, you know,” Bradshaw said. “Even if it is like the most bland, kind of like dry information, you're sort of receiving it and weaving a story in your head.”

For Bradshaw, the telling of that story — to use the language coined by Carpenter and Rainford — is a kind of liberation, hence the zine title, “Liberated Archives.”

“There's this sort of movement within archival spaces and for archivists to create work that is a sort of freeing of information or releasing of information, of memory, of history that is otherwise suppressed,” Bradshaw said.

Pages 10 and 11 of the zine illustrate that release, picturing articles, flyers, urban plans and protest letters that track the resistance to the displacement of Black communities in North Portland from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Senior Kerri Osumi, who was in charge of the housing and land section of the zine, notes how liberated archives are part of education and raising awareness.

“We bring into the now liberating — freeing — the archives and then opening it up for more research, more attention, more education on these past historical archives,” Osumi said.

For Osumi and Bradshaw, the research and education components have been major takeaways from their experience, as the project is a part of their social justice minor capstone.

“I was able to have the opportunity to kind of mesh UP and like the North Portland community — something I haven't exactly gotten through other classes before,” Osumi said.

Similarly, while Bradshaw has also said the capstone has strengthened her professionally, for her it was equally an educational experience — and one she thinks is needed on campus.

“There's so much value in really understanding Portland as a city, on campus,” Bradshaw said. “Because so few of the students here are from Portland, right, so we go through all four years of our education with basically no understanding of the history of the place that we're in.”

Riley Martinez is Copy Editor for The Beacon. He can be reached at martinri24@up.edu.