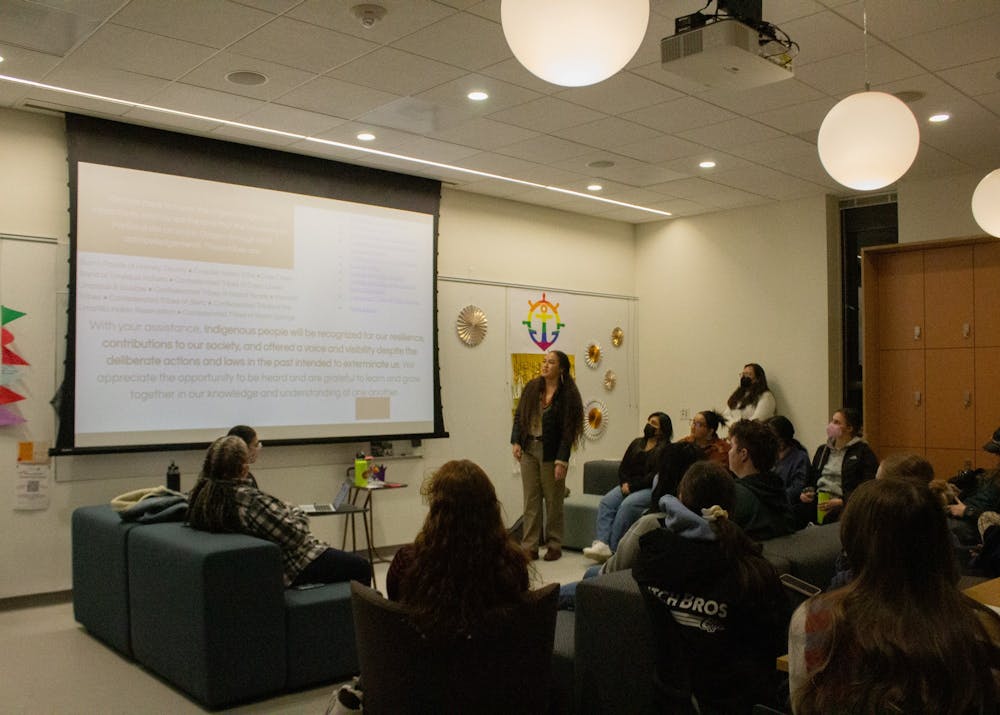

Native American Heritage month is in full swing. To commemorate the celebration, Indigenous students and faculty from the Ethnic Studies Department and Diversity and Inclusion Programs (DIP) hosted a panel in the newly opened Diversity Center. Discussion was centered around topics of decolonization, settler colonialism, injustices, Indigenous joy and resources.

Keisha DeSheuquette ‘25, the social media coordinator for Native American Alliance (NAA), opened the conversation with a few words from “The Zen of You and Me” and a call to action.

“It is time to begin in a collective viewing space,” DeSheuquette said. “That is the hope. That our discussion will permit and create a space for new students to feel comfortable in classes on campus, especially in a predominately white institution.”

“Often our communities, especially Indigenous communities are looked at in a deficit framework, but we really want to reframe that today and moving forward,” said Adeline Paguirigan, a representative from DIP.

This reframing has the focus of community building and joy at its center, working to undo past harmful rhetoric.

What is Indigenous joy?

Indigenous joy refocuses on positive aspects of Indigenous culture — celebrating and honoring connections and triumphs in the community.

“I feel joy when involved with NAA and meeting all of the Native American students,” said DeSheuquette. “When I came to UP, I was, at first, super lonely. This community has allowed me to feel more at home in Portland. I would say I also feel joy from our club. This is our biggest event, we have not had so many people show up or care.”

NAA imagines a world that is centered around these perspectives.

“For me, spending time with my family and being immersed in and practicing my culture,” said Nia Moquino ‘23, president of NAA. “When I am back home and in my culture I am not thinking about anything else. I am so stress-free and happy, I do not think about the outside world at all. Also hanging out with friends and with NAA and talking to people who have similar experiences such as me.”

What are ways that Indigenous joy can be integrated around the University of Portland? The first step in creating a more welcoming environment for students is to identify and break down the role decolonization plays in higher education.

Decolonization at UP

“Decolonization is a big word, a really powerful word,” Kamia Leano ‘24, vice president of NAA, said. “It starts a conversation. It is looking at systems or the way things are, and asking why certain systems work to help other people more than other minorities.”

Language surrounding decolonization is often superficially used and adopted by higher education, functioning as a checkbox as opposed to intentional action.

“The Portland Metro area rests on traditional village sites of the Multnomah, Wasco, Cowlitz, Kathlamet, Clackamas, Bands of Chinook, Tualatin, Kalapuya, Molalla and many other tribes who made their homes along the Columbia River creating communities and summer encampments to harvest and use the plentiful natural resources of the area,” according to the Portland Indian Leaders Roundtable, as stated on the University of Portland’s land acknowledgment.

This land acknowledgment is frequently used at the beginnings of committee meetings, staff meetings and is found posted on the University of Portland website and on many syllabi. Often functioning as a checklist item for inclusivity and diversity.

“It’s not having the intent of any of what is needed to have reparative approaches with our Indigenous students or Indigenous communities,” Paguirigan said. “It removes the accountability that this land the University of Portland sits on from having any tie to colonialism, which is really harmful.”

Landback Movement: Working towards hope

The complex relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Catholic church is being acknowledged with the rise of mass media storytelling. The Pope went on a country wide apology tour throughout Canada this last summer, to address the crimes committed against Native people through the Indian Boarding School system, dressed in culturally appropriative clothing.

“There was horrible, horrible, horrible, heinous abuse of children,” Amy Ongiri, director of the Ethnic Studies program, said.

“The boarding school system was funded by the government and run primarily by the Catholic church,” Ongiri said. “I’m saying all of this because as a Catholic institution, we have a special responsibility to be responsive to the needs of the Native American community and especially Native American students in our educational system.”

The Landback Movement is a campaign and political framework aimed at returning land to Indigenous peoples, focused on true collective liberation. Current goals include returning Mount Rushmore and all public lands in the Black Hills.

The movement is founded on a relationship with mother earth that is symbiotic, with reclaimed stewardship within Indigenous communities. Landback has seen massive success from the Daintree National forest in Australia to the management of the California Condor throughout the upper west coast of the US.

“Let’s face it, our world is in crisis, right?” Ongiri said. “How are we going to get out of it? One of the ways we can get out of it is to return to Indigenous ways of knowing. And that is what land back offers us.”

Imagining a decolonized world where land back is real and validated, is freeing, according to Ongiri.

“Not just a little bit freer, but a lot freer,” said Ongiri. “And we’re actually doing significant work of imagining a new world, a better world.”

And this better world is one filled with joy.

“For me personally, joy is found in my family and friends and being involved in communities,” Leano said. “Whether it be from NAA or going to a powwow, being around people I can connect with brings me joy. And being in nature, it allows me to be still and ground myself.”

Students can stay connected with NAA and their upcoming events through social media.

“Stand in solidarity with us,” DeSheuquette said. “Follow us on social media. We are trying to potentially host a powwow in Chiles or Collab with Lewis and Clark, so we are trying to fundraise. It will be put on in the spring or next year.”

More resources

“Get informed, by reading up on Native American History and current challenges Indigenous people face. Participate with interest in Native American events and celebrations. Create space for Indigenous voices and listen intently to the stories they tell,” according to UP’s Native American Alliance Instagram.

Current issues

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

Follow student organized creators in academia and locals on occupied lands. Provided courtesy of NAA:

- @naa_uofp

- @kianna_pete

- @uo.nasu

- @indigenouspeoplemovement

- @naya_pdx

- @naya.youth.wellness

- @amayasullivan

- @nativelandnet

Ellie Black is a reporter for The Beacon. She can be reached at blacke24@up.edu.