By Malori Maloney

In the last few months, two former University of Portland students have been publicized for suing the school after administrative officials handled their separate sexual assault cases questionably. Since news of their cases broke, I have heard quite a bit of victim blaming, not only from Kenny Smith in his opinion piece ('The 'victim' always wins'), but also from peers with whom I interact daily. I'd like to address a few misconceptions I've heard recently.

First, regarding the sexual assault case involving a former UP sophomore and a 16-year-old UP freshman, I'd like to first point out that the victim was unable to consent to intercourse because of her age and her state of intoxication. Those two details alone indicate rape under Oregon law. If you ever find yourself contemplating having sex with a drunk minor, keep that in mind.

For those whose immediate reaction to the above situation is "What was a 16-year-old girl drinking for, anyway?," please realize that a drunk person does not deserve to be sexually assaulted any more than a sober person, no matter her (or his) age. Smith wrote, "consuming alcohol is obviously a way to put yourself at risk for an attack."

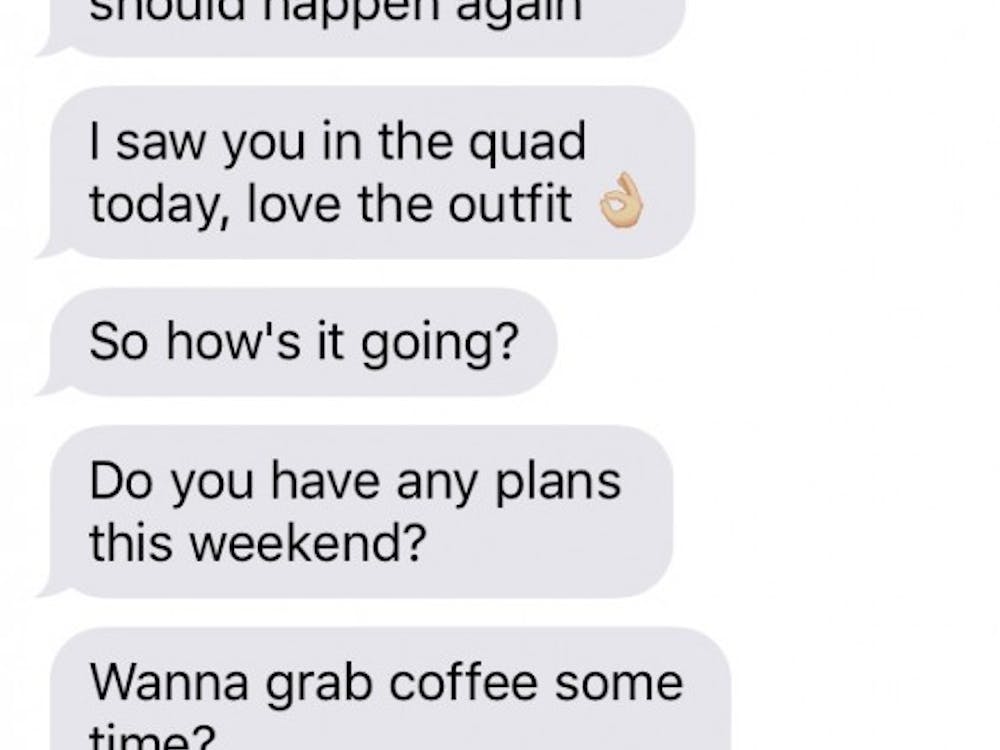

In our society, women are told that we are putting ourselves at risk for sexual assault if we drink alcohol, wear certain clothes, walk certain places at certain times, flirt too much, and on and on.

This does not mean that we should avoid all these things at all times. Contrary to Smith's assertion that "you may be a victim, but you also may have caused it," a woman who is sexually assaulted after drinking or wearing a short skirt or walking home alone at night or flirting is in no way responsible for the assault. Another autonomous person is.

If your first thought after hearing about the above case is "she probably just got drunk, had sex, and then regretted it," realize that false reporting of sexual assaults is so rare that it is virtually nonexistent.

The most current research indicates that false reports account for between 2 and 3 percent of all reports (see nsvrc.org, the site for the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, for more information). Considering that there were only five reported incidences of sexual assault at UP for the years 2005, 2006 and 2007, so statistically, less than one of those reports is likely to be unfounded. Moreover, when a sexual assault is reported to University officials (or police), guilt of the alleged assailant is not automatically assumed.

These facts should alleviate any concerns that the amnesty clause will be an 'incentive' for false accusations.

If you're one of the people I've heard say, "she's just trying to get money from the school," realize that coming forward and going through trial is a very emotionally difficult thing for a survivor of assault to do. No amount of money can remedy what has occurred and such cases are almost never about the money a survivor may or may not gain from an institution or a person who may be responsible for harm done to her (or him).

With regard to confusion over the newly instated sexual misconduct policy, it was created in order to reduce barriers to reporting. Other Catholic institutions, including Notre Dame and Santa Clara, have had similar policies for years and have seen no subsequent rise in false allegations of sexual assault.

This fact, combined with the aforementioned low rate of false accusations, makes it clear that the newly instated amnesty clause should not be a cause for concern.

On the contrary, the amnesty clause will help students by making clearer the policies of the University and letting students know that they should not hesitate to report a sexual assault regardless of extraneous details.