by Melissa Aguilar |

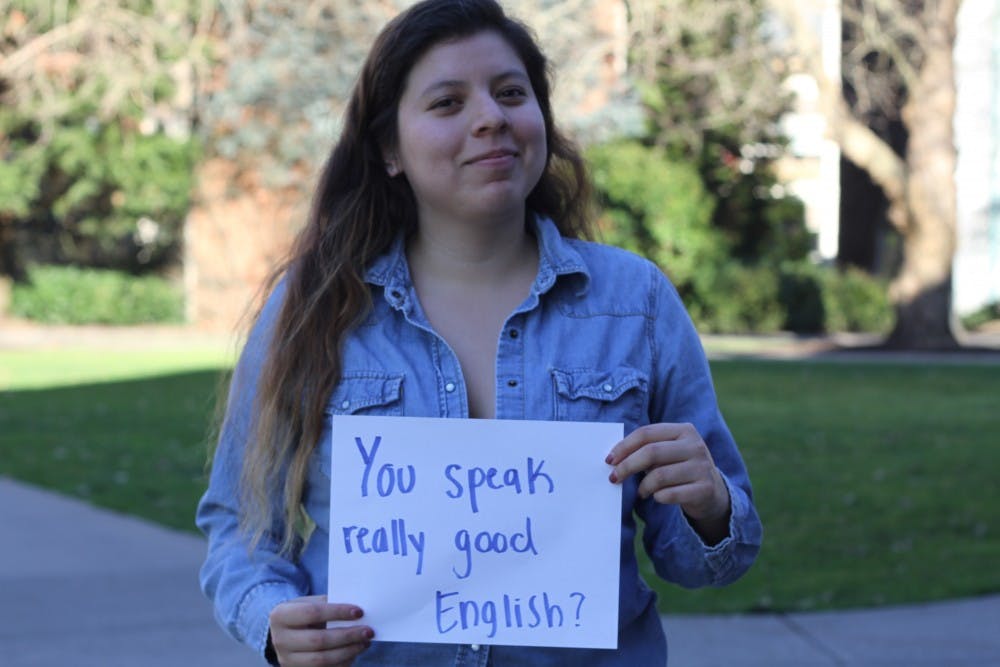

“Your English is so good.”

“You must be great at math.”

“Where are really you from?”

Asian Student Union President Jill Pham remembers a time when several students in her class assumed she spoke Chinese.

“In that moment it’s like, ‘Should I say something? I should say something,’” Pham said. “But what if it doesn’t happen the way that I want? But at the same time, if I don’t say something, who’s going to say something?”

Such comments may seem pretty unassuming, complementary even, but for students who are black, Latino, Middle Eastern, Asian, or Pacific Islander, such remarks are perceived as racial microaggressions.

What are microaggressions?

Microaggressions are simply everyday exchanges that, intentionally or not, send negative or derogatory messages to a person based on their race, gender identity, sexual orientation, ability or culture.

Spotting a microaggression is not always easy. By nature, the actions or words are so subtle, that even the person committing a microaggression may not be aware they have insulted another person.

UP Diversity Coordinator Bethany Sills says the concept of microaggressions are difficult for people to wrap their brains around precisely because the concept is so complex and relative.

“Microaggression theory is based in concerns over what doesn’t feel like racism but it clearly feels devaluing,” Sills said. “A person might not just go out there and say something derogatory but (the offended person) might say something that’s like ‘Gosh, that hurt and I don’t know why it hurt. That’s why I’m struggling here right now. Am I overreacting?’”

While a single instance of a microaggression may be troubling, over a lifetime, the inner turmoil of how to properly react to others can take its toll.

Research has shown constant exposure to racial discrimination is linked to higher instances of mental illness, as well as contributing to stress, depression and anger. Those who faced higher levels of discrimination also experienced lower levels of happiness, life satisfaction and self-esteem.

Gosh, that hurt and I don't know why it hurt...Am I overreacting?

Increasing Awareness

Senior Sharon Cortez, a member of UP’s Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA), had experienced microaggressions, but it wasn’t until she took a race and ethnicity class at UP that she was able to put a name to those instances.

“Now I’m more confident responding to them. Before, when I didn’t know what it was, I felt like something was off, but I didn’t know how to respond or anything,” Cortez said “After learning about it in class and then also just talking about it with people and just doing more research about it, I feel like now I’m more comfortable being able to respond.”

While Cortez believes student-led clubs are an important outlet for students to connect with others, she would like to see more institutional push for programs or classes to engage more of the study body.

“As a school that prides itself on learning through the mind, the heart and the spirit … all these ways we identify ourselves are very important,” Cortez said. “It would be great if we could have everyone take one cultural competency class as a core requirement.”

She added students that are not already interested in or have experienced issues due to race, usually have no motivation to get involved outside the classroom.

Sills agreed that getting students involved if they have no incentive to do so is difficult. She commended many of the Spanish professors who give extra credit to students that attend cultural events, but for those cultural groups who have no departmental equivalent, the extra support can be harder to come by.

Faculty and Microaggressions

The everyday experience of microaggressions are not limited to students of color, but also affect professors and staff.

In the 2014-2015 academic school year, out of 339 faculty members, only 30 were members of a minority group.

Philosophy professor Alejandro Santana recounted an incident in which a pair of white male students dressed up in ponchos and sombreros and donned bushy moustaches. When he asked why they were dressed that way, they said they wanted to be conspicuous so their graduating friend could spot them more easily.

A year later, Santana addressed the hurt and anger that arose when Villa Maria Hall hosted a “Latin night,” at a men’s basketball game, which directly offended two Latina students.

“For Latino/a students, this event was emblematic of the kinds of microaggressions and microinvalidations that they often endure on campus, and this is part of why this event aroused such a strong reaction from them after it had occurred,” Santana said in an email. “For many white or non-Latino students, there seemed to be general surprise, which revealed a kind of inability to foresee how this kind of event would have been seen as so offensive.”

Pham said non-white students can be made to feel alienated even inside the classroom, where they are taught by mainly white instructors.

“I think it’s troubling because I can’t look for someone on the faculty that looks like me, that has a similar background to me, that I can relate to,” Pham said “There are professors that I can talk to and connect to, but it’s not quite the same when they come from a different background. And they don’t fully quite understand the struggles, I guess, that I see.”

Students of color also face the possibility of a microaggression committed toward them by a person in power, like a professor, making for an uncomfortable power dynamic.

Cortez pointed out that the pressure would then be on the student to confront a professor.

“I feel like (microaggressions by professors) probably happen a lot because … there are a lot of white professors so maybe they don’t even know. They can’t even recognize it,” Cortez said.

“Then the student has to be like, ‘I felt uncomfortable,’ to the professor instead of the professor being like, ‘That’s not right.’”

Santana said apart from standard diversity training, he has not undergone any special training for how to confront race in the classroom.

He also said many professors seem reluctant to broach the subject in the classroom, even though he believes students strongly want to discuss the topic.

“There's also a sense of not knowing how to have these discussions,” Santana said in an email. “As a result, there seems to be an overall silence about it.”

Moving Forward

Sills and Will Meek, assistant director of counseling and training at the Health Center, created a one-hour training session for Residence Life staff to better address microaggressions as they may occur.

One of the six presidential advisory committees focuses on inclusion, but Santana said these issues just get piled on already overwhelmed staff.

While he commended those staff and faculty members that go above and beyond to increase diversity awareness, he said the University needs to increase funding and staff members who can focus on the issue more explicitly and consistently.

Last month, the University launched a new website on diversity and inclusion, which can be found under the campus life tab. The site includes a section called “Speak UP,” encouraging students to report alleged instances of discrimination or discomfort.

Sills said she hopes the site will encourage more students to talk about their experiences.

While the website is a step in the right direction, Cortez said more needs to be done so that students of all races can feel included.

Both she and Pham expressed the need for a space dedicated solely for multicultural students and activities. Multicultural clubs often host events in St. Mary’s, but the center is also used by the larger campus community.

“You have to find a balance between supporting people who are the minority but also bringing awareness to the people who don’t know,” Cortez said. “I think the fear of having a center is that people would be secluded, and I get that, but people also need to be supported.”

While those multicultural clubs host a variety of events to develop cultural understanding, Pham said the University shouldn’t rely on them to provide support for students and education.

“At the end of the day, it’s not a person of color’s responsibility to educate a fellow white person about privilege,” Pham said.

Sills agreed on the importance of all students becoming more culturally aware and more thoughtful of their interactions with people of other races or ethnicities. “I think it takes students who are really well-educated and again, have some degree of competency in the area, to say, ‘You know what? Let me reflect on how I might’ve impacted you by what I said.’ And that takes courage,” Sills said. “It takes courage as a campus community to want to engage in this conversation.”

How to avoid microaggressions

Some common microaggressions fall under these categories:

-Alien in own land: “Your English is so good,” can translate to, “You’re not really an American.”

-Denial of individual racism: “I have black friends so I can’t be racist,” can mean, “I am immune to racism because of who I associate with.”

-Color blindness: “Black lives matter? All lives matter,” can mean, “I refuse to acknowledge your experiences as a person of color are different from my own.”

-Ascription of intelligence: “You’re Asian … help me with this math problem,” can mean, “If you’re Asian, you must be good at math.”

If you mess up

-Apologize if your words unintentionally harmed someone.

-Be willing to engage in a conversation about what you can do better in the future.

-Be more conscious of the language you use and how that might affect others.

Melissa Aguilar is the copy editor for The Beacon. She can be reached at aguilarm16@up.edu.